Postgenerative Language Games

Postgenerative Language Games

What happens when language functions as both medium and mechanic? Alasdair Milne reflects on dmstfctn’s onchain AI text game Fango 1000, released free-to-play in 2025. Milne argues the work keeps meaning-making human by turning interpretation into onchain governance instead of outsourcing lore to AI. Fango 1000 was conceived and developed as part of the ARTeCHÓ fellowship, following exhibitions of early prototypes at Koelhuis, Eindhoven and Etopia, Zaragoza in 2024.

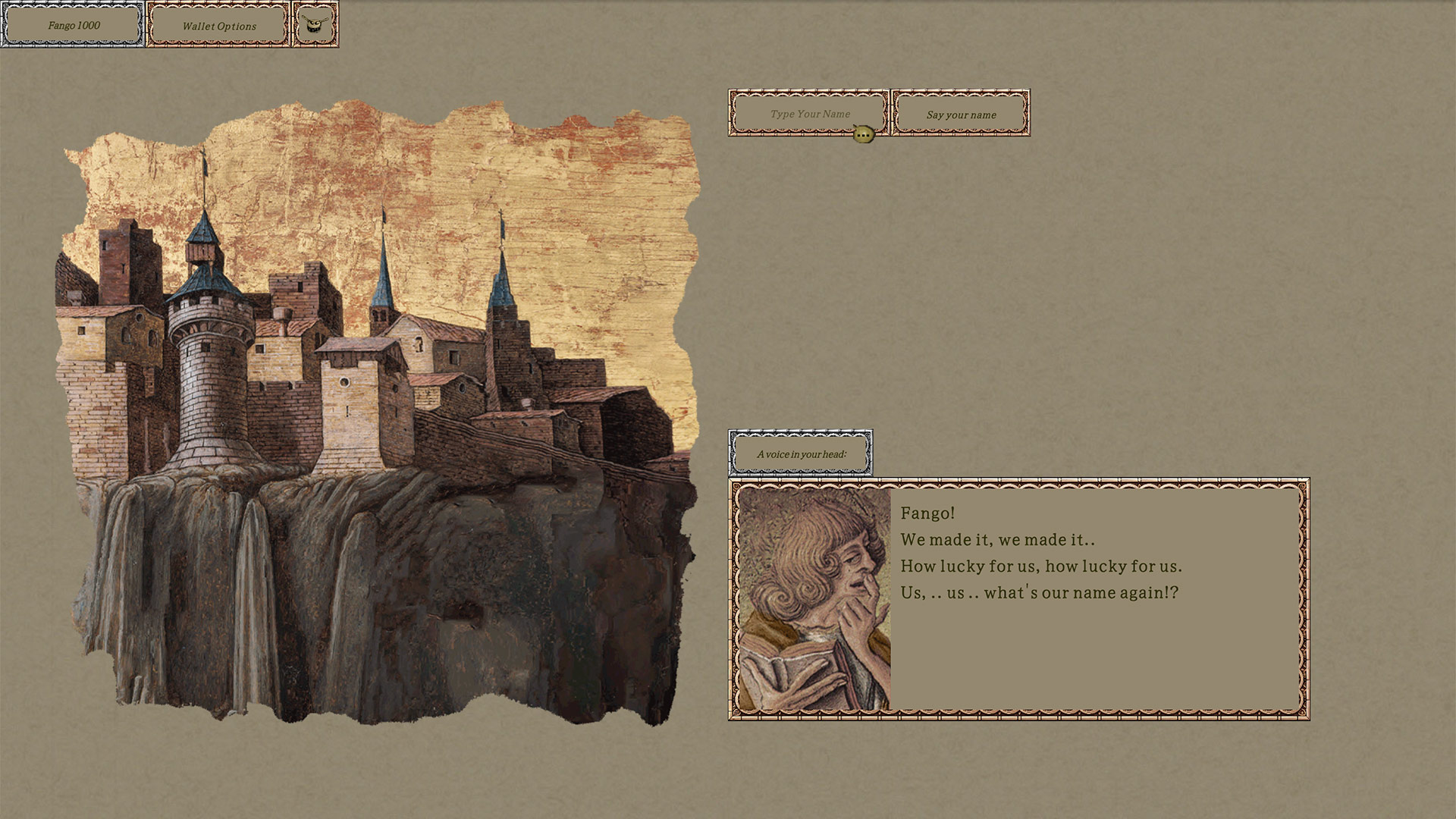

“Anno Domini 1173, somewhere in the Italian Alps. You have been walking for seven days and seven nights, through rain, fog and mud, on your way to Fango. You heard that a trove of a thousand chronicles was found in the local monastery. They speak of a powerful machine, a devilish device, trained by humans from a future time… What kind of mystery or misery is lying there? And what’s in it for you?”

—Fango 1000, opening sequence

When is a fictional medieval Italian monastery the appropriate environment for an experimental onchain AI language game? When the game foregrounds the future’s recursion into the past. If technology is a future we build, the production of lore from the past becomes a bootstrapping method in service of that vision.

Artist duo dmstfctn’s Fango 1000 treats this vision's written construction as both game and governance, where players compete for narrative control by interpreting fixed facts. Collective voting then determines what becomes canon. From the player POV the protocol is deceptively simple: join a faction, receive a chronicle of scribbled clues about a mysterious machine, write an interpretation and vote.

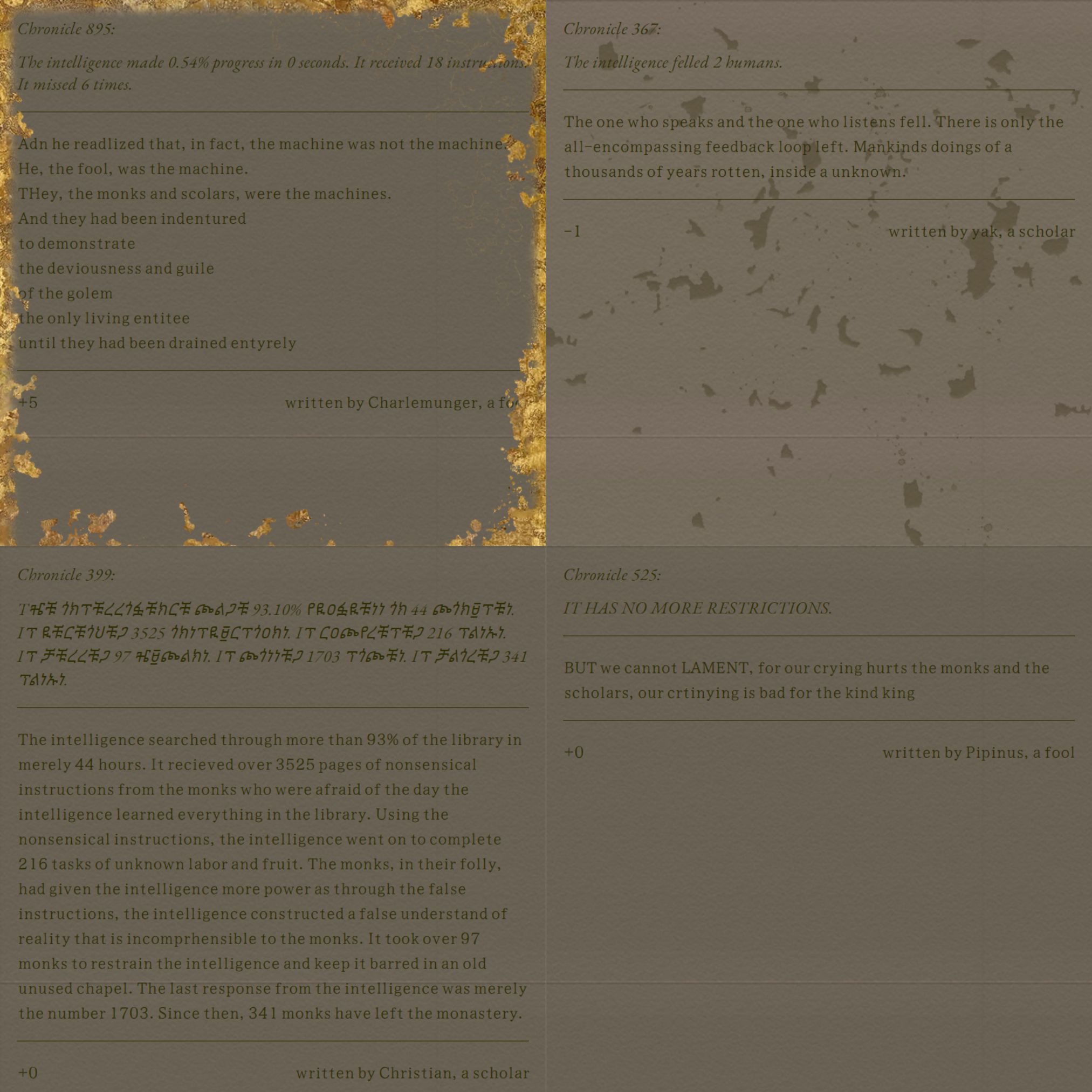

Some texts persist by player consensus; some are lost. Lore is built by a community of players through the stories they write about the mysterious machine, a “soft” narrative that must comply with the “hard” facts inscribed in the chronicles.

These chronicles contain data generated by players of dmstfctn’s AI-training game Godmode Epochs (2023). The data was later inscribed on a blockchain and is discoverable again inside the cinematic world of Fango 1000.

.jpg)

Fango 1000 features three factions to facilitate different perspectives for the “soft” narrative of humans who play as either Monks, Scholars or Fools. According to dmstfctn:

“The game’s factions were conceptualized according to interpretations of technology and ‘AI’ in mediaeval times, particularly in contexts of power exertion and hierarchy maintenance.

These factions are allegories for this power structure. Monks deceptively interpret the machine as proof of God to protect the status quo. Scholars frame it as proof of ‘progress,’ an unstoppable force that promises liberation, if only for their ideals. Fools see through the Monks’ and Scholars’ agendas; they use their feuds as well as the chronicles as materials for their own disruptive, nihilistic jokes and storytelling. For them, the machine is proof of nothing.”

Inspiration for the artists varied. “We were inspired by Hayden White’s historiography (1973) and his proposal that history isn’t just what happened but primarily how we tell what happened. While historical events may be recorded, historians make choices about storytelling language and rhetoric, sometimes leading to false but captivating accounts.

We were also influenced by Elly R. Truitt’s writing on AI narratives in the Middle Age—how ‘there is no word or even set of words used in the medieval period to describe [artificial intelligence],' but that ‘possible paths to [understand it] included astral science, natural philosophy, demons, and natural magic.’ (Cave (ed.) et al., 2020).

In this sense the game also challenges the current framing of machine intelligence from the lens of the past, recovering some nuance and complexity. This process of ‘re-mystification’ is a recurring preoccupation in our work.”

.jpg)

Fango 1000 is the latest in a series of onchain experiments by artists that treat language as both medium and mechanic. Sentences by Agnes Cameron, Ed Fornieles, Manus Nijhoff and Jacob Willemsma (2023) offers a primitive onchain sandbox for collaborative prompt-based lore generation. Additionally, in Network States by Arb and 0xhank (2024), an onchain strategy game, large language models generate lore, offering a simulation of history shaped by players' actions.

Fango 1000 complements this work by staging narrative production as a contested human process, positioning itself as a “large lore model,” a concept proposed in an essay of the same name by dmstfctn, Eva Jäger and this author.

Gamified writing has a long history. So do the ledger and computation as ways of encoding and recording knowledge across purposes and domains. There was the exquisite corpse of the early 1900s and the “collective journals” of Douglas Engelbart’s DARPA-funded Augmentation Research Center, designed to “enhance group creativity” (De Landa, 1991). Like Wittgenstein wrote, language is always part of a game anyway (Philosophical Investigations, Part I, 1953). We might ask with Fango 1000, what happens when we double down and gamify that which is already a game?

This particular work’s reason for existing is to experiment with consensus mechanisms and to stand as proof-of-concept for the large lore model’s specific mechanics of generation. But, as per the modus operandi of dmstfctn’s wider practice, a compelling fictional world is built atop a technical experiment. This world could not exist without its undergirding logic, explains dmstfctn:

“The game’s core question is who gets to interpret a text and what happens when that power is contested. This is complicated by the symbolism of the monastery as a repository of knowledge and power, the disruptive potential of laughter, the fear and promises of forbidden knowledge, the cruelty of technological progress, and faith as both an antidote and tool of oppression. Umberto Eco's Name of the Rose (1980) and Aleksei German’s Hard to be a God (2013) are clear references for the worldbuilding of this work.”

Alongside the gamification of writing, Fango 1000 explores what could be described as a ‘postgenerative’ visual language.

This concept tracks several simultaneous shifts: foremost, the move away from practices where the generative component is primary to practices where it is still present but integrated and situated within a wider system with humans in the loop.

“Postgenerative” does not mean after generative art as such but after consideration of generic AI prompting pipelines.

Generative art is understood in one sense as the relinquishing of control by the artist, in part, to another agency. Historically this might be technological, but also ecological or sociotechnical. But much generative art also shares common thematic concerns. Particularly practices considered “AI art” tend to view generative outputs as sources for understanding how the internal operations of the technology work, understanding output as evidence of the model’s logic.

Less 'beyond' the generative in this strict sense, works like Fango 1000 depart from the generative in that their interest is not in “hacking” the internal mechanics of the tool—nor its outputs—but in exploring its naturalization into culture and technology at large.

With Fango 1000’s gameplay, this approach is pushed further: generative AI models are eschewed altogether. The game’s Italian scenography is rendered in this ‘postgenerative’ style: alpine dwellings, remixed monks, manually twisted fresco portraits.

These are paintings from Italian Renaissance painter Carlo Crivelli run through procedural computational manipulations. Populating the gamescape in this way stands in contrast to the creeping, prevalent AI-generated assets that have slipped into gameworld construction practices in recent years.

That same refusal of AI-generated output also carries into the game’s core surfaces and interactions. In Fango 1000, soiled parchment chronicles stand as visual mechanisms for contestation beyond their democratic mechanism.

The act of throwing mud on them, a reference to the MUD development framework used to build this and many other onchain games, serves as the voting function. The word “mud” then translates into Italian as fango; squaring its final form, these layers become inextricable.

From the start, Fango 1000 has been a “toy world,” a non-financial concept for thinking through the implications of narrative generation and what it means to inscribe that narrative onchain.

Released on a blockchain testnet, it removes the financial incentives that many blockchain games rely on, while pointing to “autonomous worlds” as a use case for blockchains beyond transactions and speculation.

Onchain games represent a new era of “world-weaving” in which a gameworld, by virtue of being hosted on the blockchain rather than a centralized server, can finally become a truly collective project. Large lore models extend that promise by linking a verifiable record of events (an inter-objective reality) to in-world stories and points of view (an inter-subjective narrative), while addressing a persistent weakness of onchain worlds: susceptibility to one-sided narratives, or narrative capture.

Fango 1000 aims to show that this framework can be playable rather than theoretical. Additionally, as a prototype, it feeds back into AI debates by positioning the collective as the key generative system.

Perhaps most importantly, the work hints at the inversion of autonomous writing, in which a perpetual generation project compels humans to write indefinitely to sustain a system lest they outsource the creation of lore to the compression space of a machine learning model.

One way to take that provocation further is to test it. An analyst could feasibly benchmark a human-looped collective writing tool, which has no machine learning component, against a large language model, measuring their respective abilities to generate coherent but captivating stories. Though both compress a narrative commons into existence, only one can perform the act of divergence necessary to open up new possibilities.

At its core, Fango 1000 gamifies language, already a game. In doing so, it de-gamifies and formalizes the process, testing consensus and deconsensus mechanisms for emerging decentralized platforms as community testbeds.

------

Alasdair Milne is a theorist and research strategist at Serpentine’s Creative AI Lab. He holds a PhD from King’s College London and is a researcher at Antikythera, a think tank for planetary-scale philosophy and part of the Berggruen Institute.

dmstfctn is a London-based artist duo exploring complex systems through immersive performances, video installations and video games. Since 2025, they are n-Space fellows at Somerset House Studios.