Sasha Stiles and Martha Joseph on Language as Technology

Sasha Stiles and Martha Joseph on Language as Technology

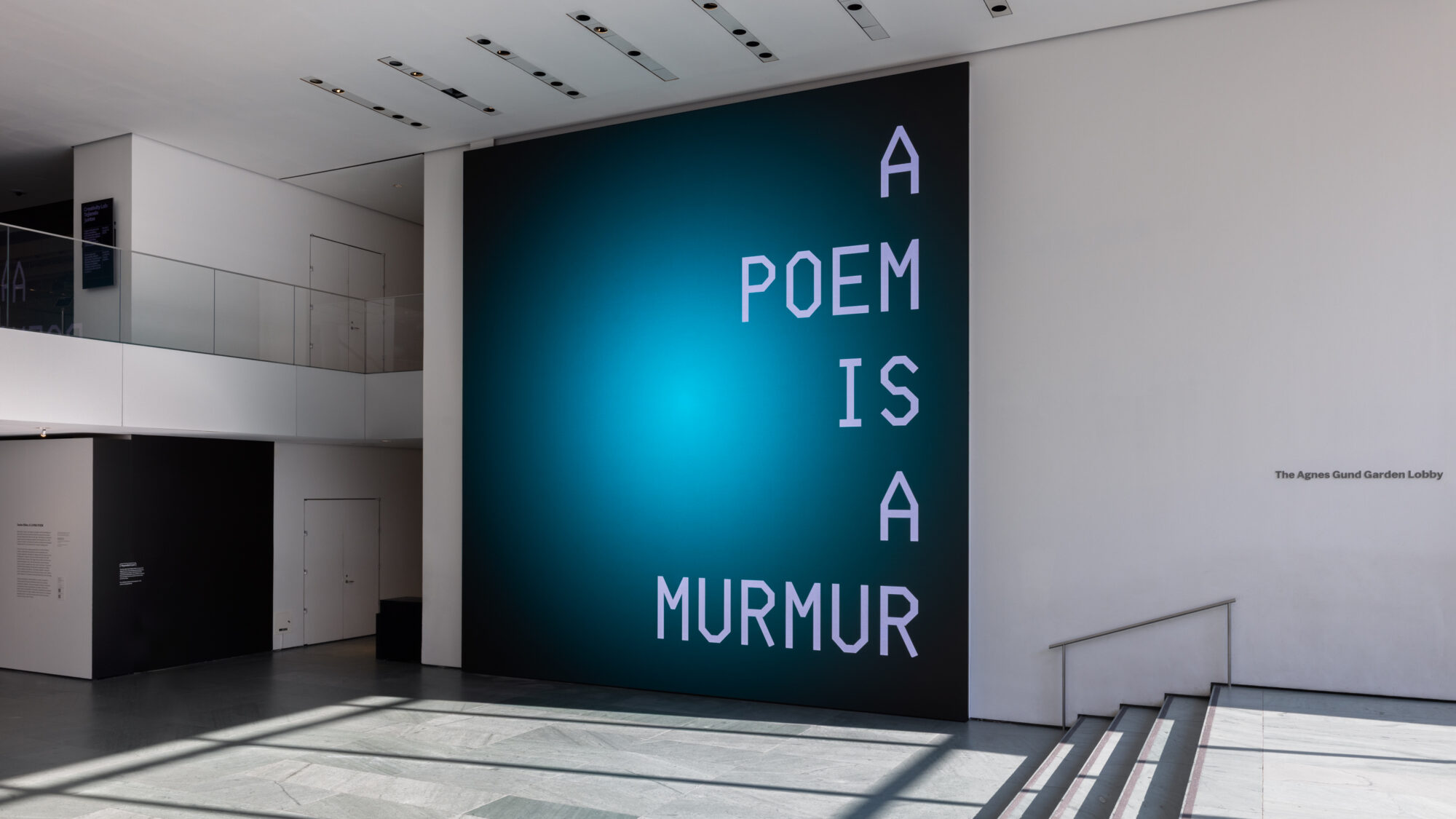

Language artist Sasha Stiles’s A LIVING POEM is on view in MoMA’s Gund Lobby from September 10, 2025. The artist speaks with the museum’s Martha Joseph, Associate Curator, Department of Media and Performance and Peter Bauman (Monk Antony). They discuss the work in the context of poetry as technology, generative performance and language’s voice in the time of AI.

Peter Bauman: Let’s start with how this exhibition began. When did you first discuss it and what set things in motion?

Martha Joseph: Both Stuart Comer, Chief Curator of Media and Performance, and I were familiar with Sasha's work. Sasha even had a pre-existing relationship with MoMA: Madeleine Pierpont, who is overseeing MoMA's Web3 initiative, had asked Sasha to participate in MoMA Postcard in 2023, a blockchain-related project, echoing the history of mail art. Then Stuart and I became involved with the program for the Hyundai Card Digital Wall in MoMA's lobby.

Some of the previous exhibitions for the wall were spearheaded by Michelle Kuo and Paola Antonelli, who started building this program with a focus on generative, web-based work. Given the specificity of the screen and Sasha's ability to work on that scale, Stuart and I both had an instinct that they could be the right artist to present for that space. Sasha had done a project at Outernet London, which was immersive and used Cursive Binary, other text and sound. I didn't experience it in person until later but I reached out to Sasha to do a studio visit.

Peter Bauman: What did you discuss at the visit?

Sasha Stiles: It was late 2024 or early 2025 and it was so lovely having you out to the studio. I'm afraid I probably just went into way too much detail about many esoteric things. But we had a wonderful conversation and spent time sifting through various ideas and concepts.

I didn't know what, if anything, would come of it. It felt stimulating to be able to brainstorm with someone else who has a lot of familiarity with the things that are near and dear to my heart.

We talked quite a lot in those first conversations about performance and digital art—generative art as performance, which is something that I've been thinking about and working on for a long time.

That really resonates for us both. Thinking about voice, which is also very important in my work as a poet, working with language. I think both about voice in the sense of text and language, being writerly, but also as an expression of language and its materiality. Voice can be human, synthetic, augmented: all these different things.

Peter Bauman: You brought up performance and voice, which points to Martha’s curatorial experience at MoMA, centered around performance, especially sound. Martha has long advocated for the act of listening, which is also a central element to this project. I'm wondering how you see Sasha's A LIVING POEM extending that lineage of listening now to AI-mediated poetry?

Martha Joseph: It's a great question. As you pointed out, Sasha, my interest in performance stems from its ephemeral nature.

Similarly, my interest in generative media art is because it shares that ethos, the idea that every encounter is unique.

As reflected in the title, A LIVING POEM, this work gestures to your poetry as not being a fixed text but something amplifying a certain liveness. At the same time, it’s problematizing certain assumptions about liveness because it's also this human-machine collaboration. I was really interested in your practice for that reason, Sasha.

Technology has so often been a tool for experimenting with voice in electronic music and the performing arts, as well as in experimental arts, visual arts, digital arts. Your relationship with technology opens up this fractured idea of self and consciousness.

Sasha Stiles: It's really important for me to situate the work that I'm doing with poetry in the context of thinking about language as a technology in and of itself. That's something that we've talked about, Peter, a lot.

Poetry often is cast as this quintessentially human art form. But poetry is also this technological invention, this very precisely fully engineered form of language that we invented in order to share our innermost feelings with other people, to externalize what's internal, to articulate what's not even expressible to us.

I think about poetry as a technology of consciousness. It's something a lot of folks in the technology and creative coding sphere have thought a lot about, too. There've been many interesting poetic language experiments done by technologists and computational artists over the years, like Christopher Strachey’s love letters in the ‘50s or Ray Kurzweil’s AI poet in 2000. There's definitely some resonance between all of these things that I've always wanted to excavate further in the work that I do.

Part of that has been thinking about how technology is transforming the way we express ourselves. How technology allows us to see and feel in real time the way that language has always evolved but now even quicker than ever before.

We have all these new technologies like large language models and blockchain that are enabling us to connect with other people in new ways: to collaborate, to create community, to network our imaginations. To me, being able to synthesize that through poetry has been a meaningful and organic medium for a lot of these interests and concerns.

Martha Joseph: The way you think about the structure of the work for MoMA feels fundamentally related to performance as well. You often refer to the core text as a libretto, which is interesting to me because it's this musical term that has a new life in this other way. Could you share more about that structure?

Sasha Stiles: We talked for a long time about what the title of this piece should be. We had been noodling around on this phrase of language as a living system across various conversations.

That’s an unlock for me: thinking about the liveness of all of this and the fact that every time you say a word, even if it's a word that's been said millions of times before, you're putting it in a new context. You are reframing it. Same thing with poetry.

We memorize and recite poems not to have the same experience over and over again, but in order to have a key that enables us to unlock different areas of feeling or to discover something new.

Every reader who encounters a poem is bringing in their own life experience and that transforms the core text of the poem into something unique. That's all at the heart of A LIVING POEM, which also integrates many themes of algorithmic recursion in different ways.

The text itself is an AI-powered long poem cycle that I've created with my AI co-author, my long-time partner in crime, TECHNELEGY. We approach this project as an opportunity to begin a dialogue with a lot of the language artists in the museum's collection who've been such an inspiration, such a formative influence on me over the years.

We want to look at how approaching their work repeatedly and in different ways might reveal new aspects—different facets of the trajectory of text-based art over the years. Using AI as a way to refract this history of text-based art was one layer. That created this foundational poem, which I think of as a core text: a generative manuscript that continues to evolve, revealing different facets of the project.

It's more than a poem; it is a system of language.

To create something for the MoMA wall, translating this concept into an experience in that space, the next step was then to take this source code and manipulate it. We used it in tandem with additional coding to bring various text arrays to life, lines of AI-generated verse, to bring those into resonance with each other. We took all the writing that TECHNELEGY and I had done together thinking about MoMA's collection to throw that all into this computational pot.

We then used a layer of code to infinitely regenerate a new poetic experience that is about language—that is fueled by language in different ways. We had a reflection on all these considerations: about text, language, voice and performance.

Rather than concretize all that into one finite performance, one finite piece, it made sense to have it be this infinitely generative experience.

Every time a visitor encounters it, there are some core pieces that are fundamental that are holding it all together, like a scaffolding, but the actual execution, the performance of it, is always fresh and always changing. It will always be totally of that moment, not to be repeated again, which I find really exciting and also really nerve-wracking—kind of scary.

Peter Bauman: You’re using contemporary tools to remind visitors of poetry’s ancient roots in recitation and embodiment. That, again, connects to Martha’s curatorial work, which consistently foregrounds embodiment and audience presence, encouraging viewers to slow down and become part of the work itself. Were you conscious of that with Sasha's A LIVING POEM?

Martha Joseph: Sasha and I have talked so much about this. The idea of slowing down for an intimate experience for a work in MoMA's lobby is a challenging task given the volume of visitors that go through that space every day. As our conversations developed, we spoke a lot about the site-specific nature of the work and how we could find other ways of extending your personal experience with A LIVING POEM to encourage close listening and looking.

One major aspect of that is the soundtrack, which was developed by Sasha and their studio partner, Kris Bones. One solution that we came to in the chaos of a lobby is the ability to stream the audio on your headphones while you're physically in the site. We also are actively working on other ways to engage with the work while not physically on-site, like streaming it from home.

Sasha Stiles: What you were both saying about the sound of this piece and the haptic, sensorial experience is super interesting to me. Peter and I have talked before about our shared interest in looking backwards as well as looking forwards, about the origins of poetry, language and oral tradition.

A lot about what I'm trying to do now with digital tools is to reengage our print-forward literary culture with where it came from: an embodied, immersive, participatory experience of language.

Part of it is thinking about the wall and this amazing screen in the MoMA lobby as a performer itself, a next-gen poet that is here to retell this AI epic.

Maybe this long poem is about what it means to be on the cusp of this new modality of being human and to engage not just through one sense but through many of the senses that our digital technologies are allowing us to access.

There's a sense of it that is very auditory and visceral. At the same time, we considered the materiality of language from a visual standpoint: the look of language, the feeling of a word appearing on screen in a certain color versus another color, moving across the screen, disappearing, accruing many meetings through reiterations of a phrase or retyping itself.

All these things are germane to the semantics or the meaning of the poem as well. It's very important to be able to think about it that way, as a full-bodied performance. There's a lot of versatility to it, responding in a way that feels right in that particular moment in time for you.

Martha Joseph: Another phrase we've been using to describe this is “poem in residence,” which I like very much because it gives you a sense of the agency of the poem, the lived-in quality of the occupation on the screen.

Peter Bauman: Let’s come back to the poem’s agency but something that’s come up a couple of times is the power of looking backwards to understand today. Sasha, I'm incredibly grateful that you are the only co-contributor to the Generative Art Timeline, where you included important moments in language art. Can you talk more about how looking back to the historical text-based work from MoMA’s collection informed A LIVING POEM?

Sasha Stiles: A lot of my practice owes to the fact that I've been writing poetry and reading poetry my whole life.

I've also always been in love with language art for as long as I can remember, drawn to the intersection of these two things: the conversation that the word and the image have with each other.

I grew up with formative encounters with works by people like Bruce Nauman, Barbara Kruger and Cy Twombly, maybe above all. If you were to stop me in the street and ask me, "Who has inspired you and formed the direction that you would take as an artist?" I would rattle off a list of text-based artists, incredible voices who've thought in very unique ways about this intersection of language and the arts.

When we started thinking about A LIVING POEM, the idea of influence and inspiration arose: how that works for human artists and how that works for AI. All human beings, not only artists, are an assemblage of our lived experiences and our encounters with other people, voices, artworks and books over a lifetime. That all forms who we are and how we move through the world. As an artist, my voice and my vision are what they are because of these specific texts, artworks and installations that I've encountered.

That's something that's come to the fore for me a lot in my work with artificial intelligence. Creating a lot of the customized language models that I work with involves thinking about what data should go into these systems to influence the outputs. What is inspiring the text that comes out at the other end of this mechanic mind?

Much of my work in this area has been about pulling together that pool of data and looking at how it transfigures and morphs into something that is a unique or an original reflection on those ideas. That's the process of art, of generative output in many ways.

When we were conceptualizing this and thinking about how inspiration works, it made sense to go into the archives and work with Martha, as well as another amazing curatorial associate, Juyeon Song, to pull together an exhaustive corpus of the works in MoMA's collection that have to do with language, as well as works that have to do with computational creativity and poetry. Through this process, I’ve been able to engage with them through my alter ego, as well as in the way that I've come to know them over the years as a more analog poet.

I started this poem process by taking my TECHNELEGY data set, which I port with me wherever I go, and then appending it with variations on this research data from MoMA’s collection. It’s taking that fact-based list of titles, descriptions and materials and using it to create little jumping-off points for myself. How Jenny Holzer thought about language—as something that helps us live and survive—becomes the seed of a poem.

Peter Bauman: We’ve talked about the rich artistic inspirations for this work but I'm also curious about the theoretical inspirations. Sasha, you mentioned language-as-alter-ego and Martha mentioned the poem’s own agency, which reminds me of postformalist ideas of language as constructed and never fixed. This ties into posthumanism, which others and I have described as Post-AI Art. To what extent do you see A LIVING POEM as part of a posthumanist tradition?

Sasha Stiles: I was just in Montreal, where I had the experience of watching my friend Harry Yeff, a beatboxer who works with technology, performance and AI. He used this amazing phrase that I've been thinking about for the past three days: AI as articulatory intelligence. For me, both poetry and AI have this in common: they’re ways of helping us give voice to things that we might not be able to recognize otherwise.

We need AI to start making sense of this new world that we're moving through, this posthuman, or more-than-human world. I think a lot about the idea of posthuman poetry and AI poetry as engaging not just our human senses but also our cyber-sensorium. It helps us get in touch with emotions that we don't even know we have yet as increasingly hybrid creatures.

The feeling that I get from projects like A LIVING POEM and other work that I've done with technology over the years is that something is being surfaced through these generative outputs that I would never have written or painted or drawn or designed or sculpted on my own.

There is something emerging, not just the systems and the tools, but the processes that they enable. It’s all trying to reveal something to me about where we're headed. It's something that poetry, in its current form, might not have the capacity to reveal to us.

Martha Joseph: Sasha, can you talk more about Cursive Binary and the other fonts you use? What’s their relationship to the aesthetic decisions that you are making in the piece with respect to color? It's really nice that in the work, the text is forefront. But there are small variations, which are very intentional, and each of them, I sense, has a strong meaning for you.

Sasha Stiles: I wanted to revel in the language and not shy away from slowness, finding the moment and the time in the space to sink into the language itself and sit with something that looks familiar—but is deeply strange.

It feels instantly recognizable but it is also being written by a nonhuman mind and might mean something very different coming from that point of view. I want at certain points in the poem to present very simple phrases, encouraging the viewer to sit with it for a minute, to revel in the strangeness and what, in the context of this project, it might mean.

Sometimes that's a matter of a pulsation of that word or changing color because that also changes its emotive qualities. All this dynamism is being powered through AI as well, through AI-controlled color tweaking and generative approaches to palettes and animation.

The font Cursive Binary is so important to me because it’s a tether to the human hand—the act of writing, scribing pencil to paper—which is the core of what I know language to be. It’s tethering the human hand to the language of today, the lingua franca of our time, which is binary code, machine speak.

Bringing those together, especially in this context, felt critical because it is this fusion between the visceral and the virtual in a very simple visual statement. But it's also this deeper poetic metaphor that when you see the zeros and ones that machines use on a daily basis to power our entire lives, you’re seeing them rendered in a human hand. To me, there's something still very touching about that.

Seeing it up on this screen at scale puts in perspective the reasons why I set out to start translating poetry into Cursive Binary in the beginning: to treat it like a place to archive and preserve some of my favorite moments of poetry and ancient poetry, as well as bits and pieces of my own technologies writing.

Being in the presence of it and being immersed by it is a very important aspect of the piece, too. The quality of being there in front of this screen, being dwarfed and humbled by the space that you're in.

Martha Joseph: A new aspect of the program for the digital wall is a partner screen in Seoul with the same exact dimensions, thanks to Hyundai Card. We've simultaneously been preparing for exhibitions in New York and Seoul, where it will be on view for the same amount of time. Sasha will also do a poetry reading in Seoul later in September. There's something unique about this digital art form: it can live simultaneously in both places, synced in terms of temporality, accessed by audiences all across the globe.

Sasha Stiles: It's something that language has always been able to do so it's the perfect way to present and to experience this work. I'm so happy that we get to play in all these different ways and experiment with how this poem takes up residence. Because it is this multifaceted, infinite, virtual poem and poet, it can be in multiple places at once.

This work can do what a book has always done, which is to have many different readers in different locations at different times.

To me, one of the joys of this project has been to think about the liminality of the art side of this, the singularity of this piece as an artwork but also that it is a poem that I get to publish with MoMA. We get to then go out into the world and find its readers wherever they may be.

Getting to experiment in this way with the history of MoMA’s collection epitomizes to me the new ethos of generative art. To be able to sit in the lobby on my computer playing with what this performance could be and working with MoMA to bring it to life demonstrates this movement of digital art and blockchain that we're all part of in different ways.

We're thinking about things in a collaborative, experimental way. We're building new things that maybe don't exist and giving ourselves the grace to try things that we might not have a template for.

-----

Sasha Stiles is a language artist and first-generation Kalmyk-American poet and AI researcher. Her award-winning work combines text and technology to explore what it means to be human in an increasingly posthuman era. Her project A LIVING POEM is on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, from September 10, 2025, through Spring 2026.

Martha Joseph is a curator in the Department of Media and Performance at The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Peter Bauman (Monk Antony) is Le Random's editor in chief.