Hans Ulrich Obrist on Exhibitions as Living Organisms

.jpg)

Hans Ulrich Obrist on Exhibitions as Living Organisms

Hans Ulrich Obrist spoke with Peter Bauman (Monk Antony) about the link between generative art, cybernetics and his do it exhibitions. They discuss how these ideas shaped the famed curator’s more open, evolving approach to his craft.

Peter Bauman: I originally reached out and we started this conversation because I wanted to chat about connections you saw between generative art and your do it exhibitions from the 1990s.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: What is interesting is this idea that there is an autonomous system. Either the whole thing or part of it has been created by an autonomous system. That was always interesting to me in an analog way. My entire adolescence was pre-Internet, from ‘68 to ‘88. In 1989 came Tim Berners-Lee, whom I actually got to meet often since I'm in London.

Already in the pre-digital age, I was thinking about these autonomous systems and the negotiation between organization and self-organization.

For me, it has to do with a certain discomfort; I would say an innate discomfort with this antiquated idea of the curator.

PB: Can you talk about when that resistance to the traditional role of the curator arose and how that shaped your early exhibitions?

HUO: I started to curate shows when I was a teenager, like in my room when I went to school. I had a postcard museum inspired by Aby Warburg. That was obviously quite controlled because I just selected the images; I created the junctions, the connections. That began in Switzerland.

Then I got a grant in my early twenties from the Cartier Foundation. I spent a lot of time in France because I also befriended artists there like Christian Boltanski and Annette Messager. Quite soon, when I would go to parties, dinners or to a club, people would ask, "What are you doing?" and I would say I was "just the organizer of an exhibition" or "just the curator."

People would say, "Ah oui, le commissaire d’exposition." The French would use this term. For me, that was always sort of police vocabulary in a way. And it's not only police vocabulary; it's also very top-down, le commissaire.

Obviously the entire profession is somehow top-down because a curator makes a checklist: what is in and what is out. The curator or the director decides on that early on. Then it's a closed system; it's a closed list. You basically execute it. Already, as a teenager and in my early twenties, I found that sort of limited because it lacked the adventure of a journey into the unknown.

I was very interested in this idea of complex dynamic systems and feedback loops. I would say that was somehow a breakthrough. Always, I think, when we are young, we look for models; we look for toolboxes.

Honestly, I don't believe in genealogy. It's more like when Alexis Pauline Gumbs wrote this great book, Dub: Finding Ceremony, which covers dub poetry, about Sylvia Wynter. She explains that her whole thinking comes from Sylvia Wynter but that it's not a genealogy. Sylvia Wynter is a kind of toolbox.

For me the question is less “What inspires you?” in a linear way and more like, “What are your toolboxes?”

For myself, some philosophers and artists were toolboxes. But I didn't really find anything in the art world about this idea of complex, dynamic systems—exhibitions which would evolve and change and grow. Because for me, an exhibition was always a living organism, which is, of course, now in the digital age, obvious.

PB: How did that idea of an exhibition as a dynamic system begin to directly shape your interest in the digital?

HUO: About ten or twelve years ago, I gave a TEDx talk in Marrakesh. I was at dinner and it was late at night, midnight. Towards the end of the dinner, we were having drinks and there was a young artist-entrepreneur from London, John Nash, who said how incredibly disconnected museums are. Then John said, "You don't even have a chief technology officer."

And it was really like, “Wow, in a way this is interesting.” Because we really were not connected. We just had a website and stuff. And none of my museum colleagues did have a chief technology officer.

So he said, "We have this group with among them Ed Fornieles and Ben Vickers," who is an educator and a digital guru. He is a monastic guru also because he founded the UnMonastery and is now founding a new monastery on a mountain in the U.S.

I said to John, when he told me about this group, "I want to meet them," because I'm always curious.

We came back from Marrakesh and the next day we had breakfast with his group. I immediately said, “We need to hire Ben Vickers for the Serpentine. We need tech. And we need a visionary like Ben who drives that.” Ben set up the Arts Tech department. He was initially a digital curator.

Of course, the more we worked on these exhibitions—with Ian Cheng, the first AI project, at the time when BOB was born; with Hito Steyerl on a virtual AI garden; with Jakob Kudsk Steensen; with Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg on an AI-assisted garden—it became obvious to me.

That’s actually the first thing I told Ben years ago: “Wow, this is like my analog shows.” Basically, these artists are working with living organisms—the artwork. Ian was explaining that he loves live simulation because he disliked this idea of a loop. So he wanted a live simulation. Between live simulation and AI, there’s this idea of the artwork as a living organism.

We’ve then had a Refik Anadol show at the Serpentine. 2024 was the year of AI. We did a show with Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst, The Call.

These shows are living organisms. The show is never quite the same.

PB: The Call was one of my personal highlights of 2024 and I got to chat with Mat about it. You mentioned how you were surprised that these digital shows were so similar to your analog ones. How did this idea of shows as “living organisms” lead to the origins of do it?

HUO: It was always true for my shows since I was a student. When we developed do it, I felt it was weird to do that for the first time. I was wondering who had done it before.

I started off focusing a lot on architecture and urbanism because my research was always art, architecture, design. Because I feel like, as [Giorgio] Vasari said in Lives of the Artists, Lives of the Architects, we should not separate this. We should go beyond the field of public knowledge.

I started to meet many architects. I realized that Team 10 in the ‘50s had questioned Le Corbusier’s master plan. And I also figured out that there were people like Yona Friedman, Cedric Price and Joan Littlewood. I went to see them.

Of course the late Yona Friedman, the Hungarian-French architect, had worked a lot on this idea of self-organization in urbanism. It was the idea that we actually can't really predict how people move in a city.

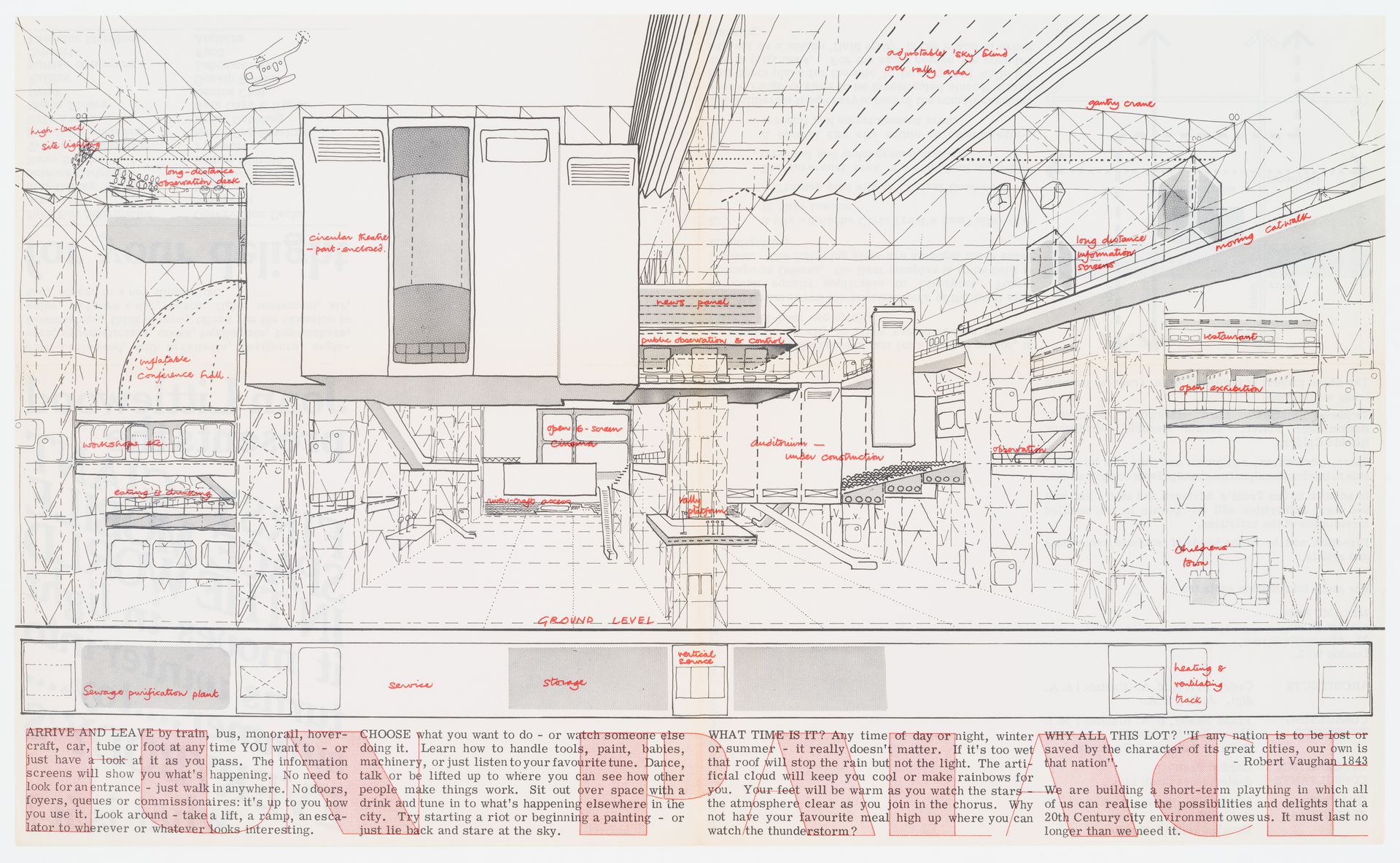

The real breakthrough came when I went to see the late Cedric Price because Cedric had worked with Joan Littlewood on The Fun Palace. That was a project which almost got realized but ended up not being realized. It was Littlewood, as the pioneer of street theater, and Price who wanted to build an interdisciplinary art center which would always evolve and change.

There wouldn't be rigid exhibitions but it could sort of flow in format. There could be an opera. The opera becomes a lecture hall. The lecture hall becomes a concert. The concert becomes an art exhibition. And then it becomes a community center.

Joan Littlewood had passed away but I said to Cedric, “You and Joan invented this.” And I asked him, “Who else was on board with these complex dynamic systems and feedback loops?”

He explained to me that they had a cybernetician on board, one of England's most famous cyberneticians, the legendary Gordon Pask. I felt like, “This is amazing that cybernetics inspired one of the most interesting museum and constantly evolving exhibition projects.”

Their toolbox was cybernetics.

PB: Can you talk more about the impact of cybernetics on your ideas of exhibition-making? The field had already helped birth digital art and AI.

HUO: It made me think, “I need to find out more about cybernetics.” I started to research and went to libraries. I found out that obviously Norbert Wiener had passed away—my dream was to meet Norbert Wiener. Sometimes we arrive too late in life and obviously that was the case this time.

But I found out the great news that Heinz von Foerster, the secretary of the cybernetic group, was still alive. In the ‘80s, I started a correspondence with him. He answered me and said, “Come to Vienna.”

He had early on noted the deep connections between science and art. He said that one shouldn't forget that a scientist, in some respects, is also an artist.

He worked with Norbert Wiener from the ‘40s to the ‘60s in the field of second-order cybernetics. He explained to me that it’s this idea that the observer is understood as part of the system—not an external entity.

And told me that he always somehow perceived art and science as complementary fields. They invent new techniques and describe them. They use language like a poet or the author of a detective novel to describe their findings.

He would say that a scientist must work in an artistic way if he wants to communicate his research—to talk to others. He’d say that the scientist invents new objects, right? For me—I found this quote from an interview in the ‘90s—I wanted to know how he defined cybernetics because I was thinking how it could influence my curating.

He said that “the substance of what we have learned from cybernetics is to think in circles. A leads to B, B to C, and C can return to A.

These are not linear arguments but circular arguments. In that sense, the contribution of cybernetics is that our thinking is to accept circular arguments. We need to look at circular processes and understand under which circumstances an equilibrium and a stable structure can, in a way, emerge.”

PB: Cybernetics, too, is so critical today with deep learning. How did you take what you learned from these thinkers—and from conversations with von Foerster and others—and embed it directly into the architecture of an exhibition?

HUO: I did start to think, “How could we do exhibitions like that?” Obviously, at the beginning, it was a bit naive but then it became a complex, dynamic system. We started do it—which you mentioned—with Boltanski and Lavier. We started them initially to help artists do instructions. Then these instructions—open scores, recipes for food, for music, for artworks—were translated into many languages and sent around the world.

I quite soon realized—and that’s where Glissant enters the picture—that this will create a kind of circular system and that it might never end. And it has never ended.

I mean, do it has been on the road since 1993. It's been over 30 years and it has never stopped. There's never been a moment where there wasn’t a do it exhibition.

It worked. It has happened in 169 cities, in dozens and dozens of countries. But I wanted it to also address what I had learned from Glissant, because I did not want it to be a homogenized globalization, where all of a sudden we are sending these instructions by artists around the world and the world just executes them.

We wanted to have that feedback loop in each city, where the local art team could realize the global instructions while also contributing local instructions, which then become global because they tour to the next city.

That’s how the thing grew.

In every city, we learned that there was also a local history of instruction art and recipes. For these thirty-plus years, we have had about six hundred instructions now. There have been about thirty books. The books are always orange, which comes from a DIY Swiss supermarket.

It was a complex thing, which came from an intuition and a discomfort about being too policing and too top-down. It came from questioning, “How could we open up?” and meeting these bottom-up urbanists. Then there was cybernetics, too.

Ever since, I’ve done this with many shows. My Instagram project is another example of that. We’ve done it also with some group shows like Cities on the Move, where we actually built a Hou Hanru city and then it toured. It became a feedback loop.

I love your initial question about do it and generativity. I've never really articulated the connection between them. I mean, I always knew that it somehow connected to generative art. It’s also interesting to think more about how generative art connects to cybernetics.

PB: Another living link to cybernetics and art is Frieder Nake, who studied under Max Bense. Cybernetics was the backbone of that European branch of computer art.

HUO: Of course. I’ve always believed since I've been in the art world from the late '80s that it's important that when there is a new evolution or a new development, we also look back at who the pioneers were.

Today there’s more information but not necessarily more memory. Amnesia can sometimes crowd the core, as we know too well in this digital age.

For me, to protest against forgetting, part of my interview project is often to go see these pioneers. Frieder Nake is my unrealized interview. And I really hope that I can do that.

What I did do in New York in 2024 was conduct a very long interview with Manfred Mohr, obviously another pioneer of digital art based on algorithms. He came out of the discovery of Max Bense and his generative aesthetics in the early '60s.

That really changed his thinking, as he told me in the interview. Through Max Bense he went from abstract expressionism to computer-generated art.

So it's wonderful that these Max Bense pupils are still around. They’re already in their eighties now but they’re still around. Then, of course, Vera Molnár I’ve interviewed and many others.

I think the history of these pioneers needs to be written now. And they need to be much, much more known to the public consciousness. Because they have anticipated so many things.

-----

Hans Ulrich Obrist is a curator, critic, author and art historian. He is Artistic Director of Serpentine in London and Senior Advisor at LUMA Arles. Since his first show, World Soup (The Kitchen Show), in 1991, he has curated hundreds of exhibitions. Most notable include the Do It series (1993–), Take Me (I'm Yours) in London (1995), Paris (2015) New York (2016), and Milan (2017); and the Swiss Pavilion at the 14th International Architecture Biennale in Venice (2014).

Peter Bauman (Monk Antony) is Le Random's editor in chief.