AA Cavia on Summoning Worlds

AA Cavia on Summoning Worlds

Philosopher AA Cavia discusses how computation has moved from rule-based programs to cognitive models with Peter Bauman (Monk Antony). They explore what this means for artists working with latent space and why creativity is tied to both technology and alienation.

Peter Bauman: I’m fascinated by how you see and describe computation changing. In "Art and Language After AI" you present a “topological view of computation” and understand it as a shift from binary, hard programming to cognitive models (e.g. deep learning) and their topology. Can you break down what you mean and what that shift—from discrete outputs to navigable space—means for aesthetics?

AA Cavia: I arrived at a topological view of computation as a result of an attempt to understand why modern conceptions of computation have diverged somewhat from the canonical view, which is that of a universal axiomatic machine, an entrenched position I call Turing orthodoxy. It turns out there’s a lot of post-war research in theoretical computer science, cognitive science and philosophy of logic which lead you in this direction.

In my account, computation is not reducible to a formal model or a machinic apparatus but is rather conceived as a way of explaining things, namely computational reason. I take computation to be essentially cognitive in character, distinguishing it from the general domain of what Gilbert Simondon once called “technical objects.” The mode of explanation which we can characterize as computational is tethered to certain logics which are only minimally axiomatic and rely on mappings called isomorphisms. The formal and physical registers of computation and their coupling can then be recast to move us away from canonical accounts. Replacing Boolean algebra as the default interpretation of voltages on a silicon chip is a prime example.

On this view, computation lacks much of the grounding you would associate with formal axiomatic systems of the kind Turing had in mind. The only real grounding available to it is the notion of realizability, which is the idea that for logical statements to be valid, they have to be effectuated as physical processes. This is a constraint which introduces an irrevocable uncertainty into logic.

Another way of putting it is that under computationalism there is always an intrinsic contingency at play until one bears witness to a truth in the form of a program. The theorist Beatrice Fazi writes about the aesthetic dimensions of this in her book Contingent Computation, whereas I come at it from a more cognitivist perspective in my writing.

Programs enact (or realize) these mappings (or morphisms) which in turn rest on a notion of equivalence rooted in topology.

This brings us on to topological foundations. It turns out topology can yield a fully structuralist mathematics. If we consider topology the view that all space has an attendant structure, then you can use a form of path equivalence known as homotopy to create a computable type theory in which spaces correspond to types and programs are paths forged in these continuous spaces.

Computation is then a matter of tracing equivalences, or else a way of forming identities, and ultimately a means of making patterns or structures intelligible.

No more, no less. The term “structuralism” may sound very rigid and restrictive at first but this actually affords computation a lot of inferential freedom, more than is canonically accepted. In this view, the machines and devices we use everyday are simply a very specific expression of computational reason, a historical example of a broader epistemic process of rendering worlds intelligible.

This brings us on to the shift from stored programs to cognitive models, which gets to the heart of what I have called a "watershed moment" in computational aesthetics.

We can think of the regime of algorithmic composition as being characterised by the key property of decomposability: the idea that we can reflect on, explain, and ultimately come to understand the output of algorithms via their decomposition into finite mathematical rules.

Consider the 'Perlin Noise' algorithm as a canonical example. This noise algorithm was produced by Ken Perlin for the film Tron and has thereafter been a mainstay of the computational arts. If you've used 'random()' in Processing, you've used a variant of it. Its outputs are manifold and varied, from clouds to water to terrain to marble and wood textures. But we can reason about them by examining the inner structure of the algorithm, which combines gradients and dot products, often supplemented by nested periodic functions, and come to appreciate the immense generativity of these elements when they are combined in a specific way. It's an incredible feat of compression that you can do all of this in two hundred lines of C.

But once we're done marveling at it, we can gain a sense of why it has the properties that it does.

In synthetic media, the complexity of these algorithms has given way to a massively distributed set of connected functions enshrined in artificial neural nets. The algorithmic decomposition of these models no longer meets the usual standards of explanatory adequacy required when assessing the outputs.

The output of an LLM “decomposes” to a multi-billion parameter linear equation. What are you going to do with that?

The mathematics is brutally simple but the complexity is encoded in the large-scale connectivity of the model and its capacity to learn the weights of those connections. So we need to engage in acts of interpretation to explain the output, and these have to operate at a different scale of abstraction, not just at the level of the transformer architecture or next token prediction, but even beyond that. This is why the “stochastic parrots” critique, merely pointing out their statistical reducibility, is an insufficient treatment.

These critiques do not adequately explain the capacities and abilities of these models, though they do help to explain some of their shortcomings. The conceptual shift from program to model then is an attempt to emphasize the fact that there has been a breakdown in the regime of composition.

In place of decomposability, synthetic media by contrast exhibits what I call a stochastic diffusivity. Think of the way that forms seem to blend into each other in generative imaging today as symptomatic of this shift. Computational processes will come to resemble more and more the plasticity of cognitive models as in-situ learning takes hold as a paradigm in AI so the idea that you have a stored program you can confidently reason about slips away. Instead you have a plurality of learning agents deployed into specific contexts, which diverge from each other by exposure to environmental pressures, even if they are bootstrapped from a smaller set of foundational models.

Peter Bauman: This shift from program to model implies a new creative space. We might think of three creative spaces: pictorial space (the 2D visible output), output space (the full range of programmed works), and latent space (the model's topological space). Since all three are essentially infinite, what does exploration of latent space uniquely offer for creatives, e.g., conceptually, mathematically, philosophically that the other two do not?

AA Cavia: I think your framing is apposite in that topology tells us that spaces are not neutral containers; they have shapes, are structured in specific ways, and possess integral logics.

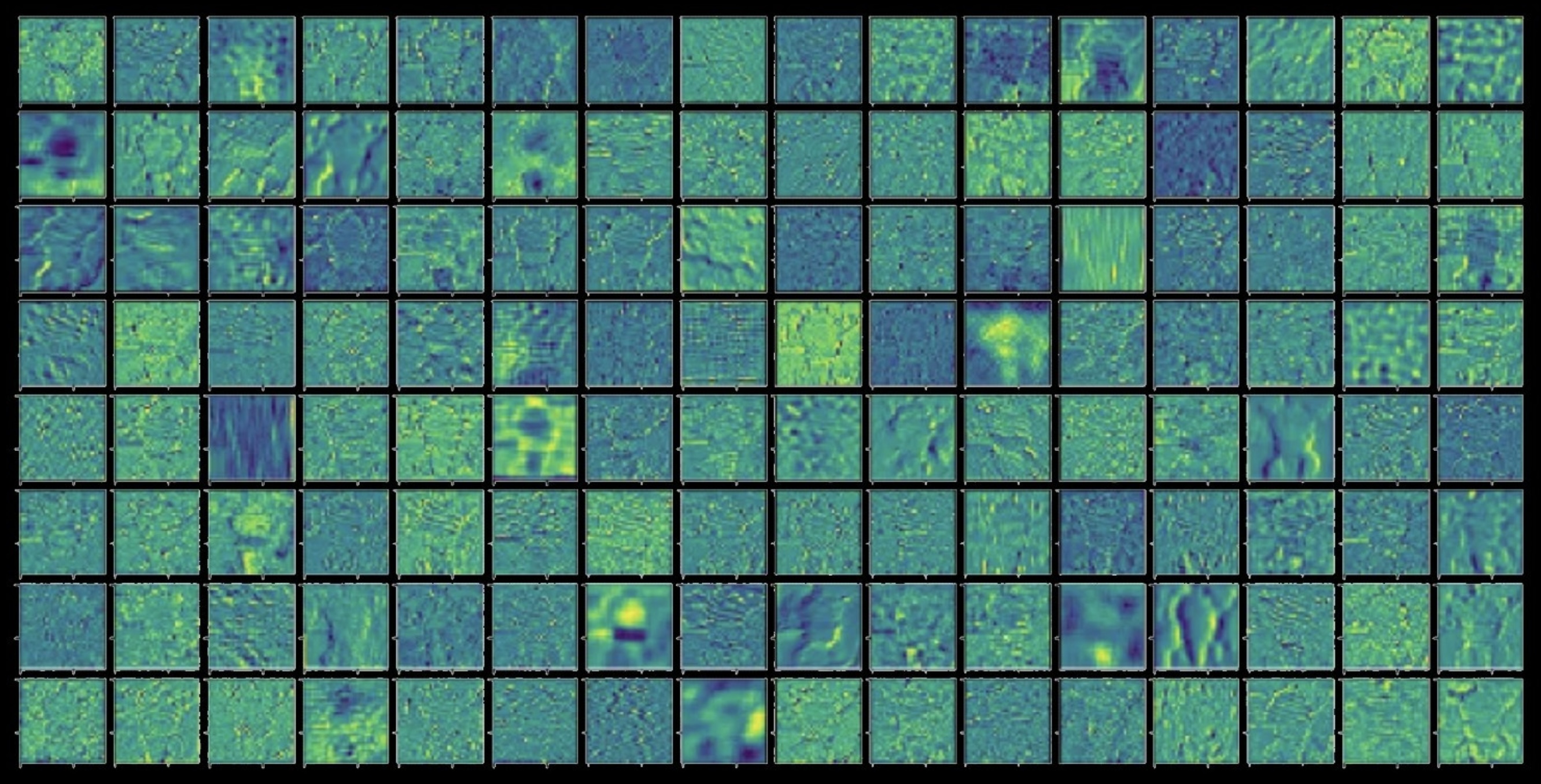

When we consider latent spaces and their pivotal role in synthetic media, we are really dealing with a broader crisis of representation, as their dimensionality evades any kind of pictorial logic. The feats of compositionality we associate with contemporary deep learning models rest largely on transformations in these high-dimensional spaces.

I liken this crisis to the shift to perspectivalism in Renaissance art, in that I think it has broad repercussions which go well beyond the field of aesthetics and into politics, ethics and epistemology.

On the topological view, navigation of a latent space is akin to interpolating points on a pre-existing manifold embedded in a space. So you can imagine it as a continuous high-dimensional surface which invites infinite exploration. It's important to note that this differs from the parameter surfaces we associate with traditional algorithmic composition.

Multmodal embeddings should be seen not in the parametric tradition so much as encodings that capture the semantics of any given modality or domain of structures. A point on such a surface is necessarily in a semantically laden space, a fact which is laid bare by the use of generative prompting techniques as a compositional strategy.

The way I would express it is that to compose a scene is to summon a world.

But what do I mean by “world” here? In the sense intended here, a world is a set of empirical, modal and normative relations which are inferential in character. The generativity these spaces present to a composer is thus on a different register to the algorithmic; it's on a conceptual register. There’s a piece by Mat Dryhurst and Holly Herndon entitled Readyweight θ (2024) which encapsulates this very nicely, in that they published the artwork as a set of concepts encoded in model weights, which can in turn be used to generate images of an “original” sculpture that they had conceived. This is why in my essay, “Art & Language After AI,” I focus heavily on the origins of conceptual art to try to understand the current moment in computational aesthetics, in particular, the theory-laden nature of composition it presents via practices like prompt engineering.

A stronger form of creativity is to be found in generating a new manifold entirely, inducing a novel embedding if you will. Those rare instances where a genuinely new domain for reasoning emerges. One example would be Andrew Wiles's proof of Fermat's last theorem, which applied the theory of modular forms to elliptical curves, which in turn opened up new spaces for mathematical thought.

Naturally, Wiles was not working from scratch, but rather the body of mathematics available to him in the late-twentieth century. Novel embeddings are always generated from raw materials (fields of structures), which in my account bottom out into the real, or real patterns, as Daniel Dennett would put it. Some examples from art that exhibit this form of radical creativity might include Gustav Metzger's body of work, Henry Flynt's notion of Concept Art or Agnes Denes's Wheatfield. In music, it’s perhaps a figure like Iannis Xenakis and the ideas he presents in Formalized Music.

In my mind, none of these figures can be said to have simply navigated the latent space of existing art practices of their times. They fundamentally altered the space in which the concept of art could be considered.

Peter Bauman: It reminds me of the sadly passed Margaret Boden's thoughts on transformative creativity. Is this radical creativity inherently alienating? In "Turing Trauma" you suggest that computation estranges us from humanist self-images, almost as a humiliation of thought. Do you see this estrangement as aligning with or challenging the posthumanist move away from human-centered concerns (creativity, authorship) in AI art?

AA Cavia: The notion of “positive” alienation, which is often associated with Hegel's account of estrangement (Entfremdung) and externalisation (Entausserung), has been active in my work for a long time. I'm interested in recovering it from the wreckage of its enlightenment heritage via thinkers such as Sylvia Wynter, Frantz Fanon and Homi K. Bhabha.

I think one can excavate remnants of this tendency further back in time even, looking to Indian philosophy, which has a lot to tell us about alienation in thought. It's a theme which first brought me into contact with the artist and writer Patricia Reed, for example, a long-time collaborator of mine who has written at length on the topic. She has an essay, “On the Necessity of Horizonless Perspectives,” which comes to mind.

This attitude is in contrast to much of the Marxian tradition, in which alienation is generally presented as a negative condition for the worker to overcome. If we conceive of art broadly as artefactual elaboration, or else synthetic composition, it seems to me by its very nature to be an alienating practice.

I would go as far as to say that creativity and alienation are inexorably coupled, insofar as all art as an activity is imbued with a kernel of technicity.

Right now, lying on my desk I have a photograph of a sculpture from Pierre Huyghe's Mind's Eye series which encapsulates this very well. It's an aggregate of synthetic and biological matter which defies any referential grounding in language that might recapture it fully into the domain of what Sellars calls the "manifest image" of the human, which is to say our lived experience.

In the “Turing Trauma” essay, I'm presenting AI, conceived as the artefactual elaboration of cognition, as a post-enlightenment project, as essentially precipitating a crisis in the concept of the human. I end the text with a provocation in the form of a fourfold assertion, intended as a positivist inversion of Buddhist philosopher Nāgārjuna's fourfold negation or catuṣkoṭi.

It states that AI (and this could be said of the entire domain of practices we might bracket under techne) possesses both a positive and negative valence: That it must both be overcome and rigorously pursued.

I see the concept of inhumanism, developed by Reza Negarestani and elaborated by myself and others, as an attack on some of the more toxic precepts of humanism, pushing back on a certain narcissism contaminating western thought. I talk in the essay about the passage from theological to scientific self-images being superseded by a properly ecological conception of the human.

I think art has an important role to play in this generational task, in that representation is inherently ecological, it necessarily takes alterity as its subject.

This decentering of the human should not be conflated with dehumanizing tendencies that center capital, empire or the war machine over human welfare. It's instead an invitation to develop new norms with which we can rethink the human and its place in our intellectual tradition, so I see it as a political project with emancipatory potential.

Seen through this lens, AI is a project of transition of the human, a transgression encoded into its origins in Turing's imitation game, a test which machines should not be seen to pass, but which instead humans are inevitably set up to fail. And in this failure of self-recognition I see some positive potential. In this sense, the only alignment problem I think we should be tending to is that between humanity and capital, a conflict in which computation has been weaponised.

In this regard, I reject narratives which posit a total subsumption of computation, or indeed any paradigmatic technology, under capital. If we look at the backlash against AI, which pits human creativity against generative models, it appears to be guided by archaic notions of creativity, which suffer from residues of said twentieth century humanism. As a result of this discourse, Luddism is rampant, particularly in the academic left. Even a cursory reading of the philosophy of technology, take Simondon's discussion on the dualism of organism and mechanism as taken up by Yuk Hui, will suggest a completely different way of approaching such questions.

The notion of authorship has been shifting continuously throughout human history of course, and the answer is never to down tools and protect what we have, but rather to forge new tools.

As creative practitioners, there are many ways I think we should be organizing against capital, including new ownership and rights models, but Luddism isn't one of them. The history of art and the history of technology are one and the same; they are intricately braided. Without the invention of a technique such as oil painting we wouldn't have Van Eyck's Ghent Altarpiece. Art is hatched in that friction between human experience and technical practices. On this point I would take heed of Rimbaud's advice: one must be absolutely modern.

If contemporary reality feels like a season in hell, the only exit to be found is in beating a path through the wildfires of postmodernity to new technicities.

-----

AA Cavia is a computer scientist, writer and researcher. His studio practice is centered on speculative software, engaging with machine learning, algorithms, protocols, encodings and other software artefacts. He is the author of one book, Logiciel: Six Seminars on Computational Reason (2022), published by &&&.

Peter Bauman (Monk Antony) is Le Random's editor in chief.