NODE's 10,000: Fast Art, Slow Looking

NODE's 10,000: Fast Art, Slow Looking

As art shifts from objects to living (continuously executing) systems, institutional infrastructure and capacity must respond. We need living institutions that can preserve conditions of emergence rather than conserving artifacts. Peter Bauman explores how NODE offers one such model, as it showcases these precise capabilities with its opening show, 10,000, by artists Matt Hall and John Watkinson, curated by Amanda Schmitt and produced by Natalie Stone.

Evolution can be slow or fast, advancing through two mechanisms: gradual mutation and sudden symbiosis, when new forms of life appear all at once.

Culture, its institutions and society evolve similarly, alternating between long periods of gradual drift and punctuated leaps when new technologies (printing presses, photography, digital computation, the internet) reorganize how we make meaning and represent our current realities. But instead of recognizing that both slow drift and sudden leaps are essential, they can be cast as opposing values.

Slow vs Fast?

Which team are you? Team slow, museum, art and everything analogue? Or are you team speed, technology, screen and everything digital? They’re opposites, you know?

After all, museums are just too slow to get the speedy digital. If anything, they may actively oppose it. Contemporary art curator and author Helen Molesworth talks about “museum time,” that the museum’s job has become resisting our speed-obsessed culture, serving as a counterweight. It’s to be “slow in a culture that has lost its mind on speed,” a not-so-subtle dig at Silicon Valley’s “move fast and break things” ethos.

But the core issue isn’t “yay art slow” and “boo technology fast,” as if they have nothing to do with one another, as if we’d rather them not have anything to do with one another. Why on earth would we want to critically and creatively examine technology?

The core issue is institutional capacity to keep up with the newest areas—complexifying, protocolic stacks—artists are choosing to explore.

As usual, artists and ideas are moving faster than the spaces they’ve traditionally occupied. Like the white cube was a response to modernism’s break with the salon’s hierarchical display, rigid taste and top-down restrictions, museums and galleries today need an equivalent response for decentralized, networked art whose medium—a running system—requires infrastructure for continuous change rather than a cave wall, er white cube, for objects.

Object vs System

So it’s not that museums or contemporary artists don’t understand the digital’s impact or simply lack screens. Walk into MoMA’s lobby. Visit ZKM or Museum of the Moving Image, whose missions include archiving digital equipment and artifacts. Consider a more nimble space, like Francisco Carolinum, site of Art of Punk, which shows that these stale dinosaurs can actually think critically about NFTs, community, digital presentation.

The challenge lies in how they think about them. These venues still consider the works mostly as fixed “digital artifacts.” Even when a coded piece is running live, it’s usually positioned as a temporary instance, presented as a stable object to be shown, wall-texted and conserved.

What gets missed is the work as a system with no final state, continuing to unfold independently of the exhibition. It's the difference between a demo video of software and the software running in the wild.

Once the medium is a running system, the bottleneck becomes infrastructure and staffing. Do existing spaces have the technical infrastructure and personnel congruent with this more dynamic, less final direction in art? But the art object has been contested at least since its dematerialization in the 1960s; relational aesthetics further diminished its authority in the 1990s. Rather than the point being the death of the fixed object, it’s about solving for the birth of art forms designed to never die.

NODE and 10,000

NODE is an experimental response to that mismatch. It posits that the problem isn't art world ignorance of the lazy claim of our increasingly digital condition; they get it; we all get it; it's no secret. Instead, NODE emphasizes building the necessary operational capacity and flexibility that traditional venues can lack.

NODE is responding to a new type of artwork now possible due to said condition: living, networked, protocolic art that executes, updates and accumulates, producing new aesthetic events through continuous engagement.

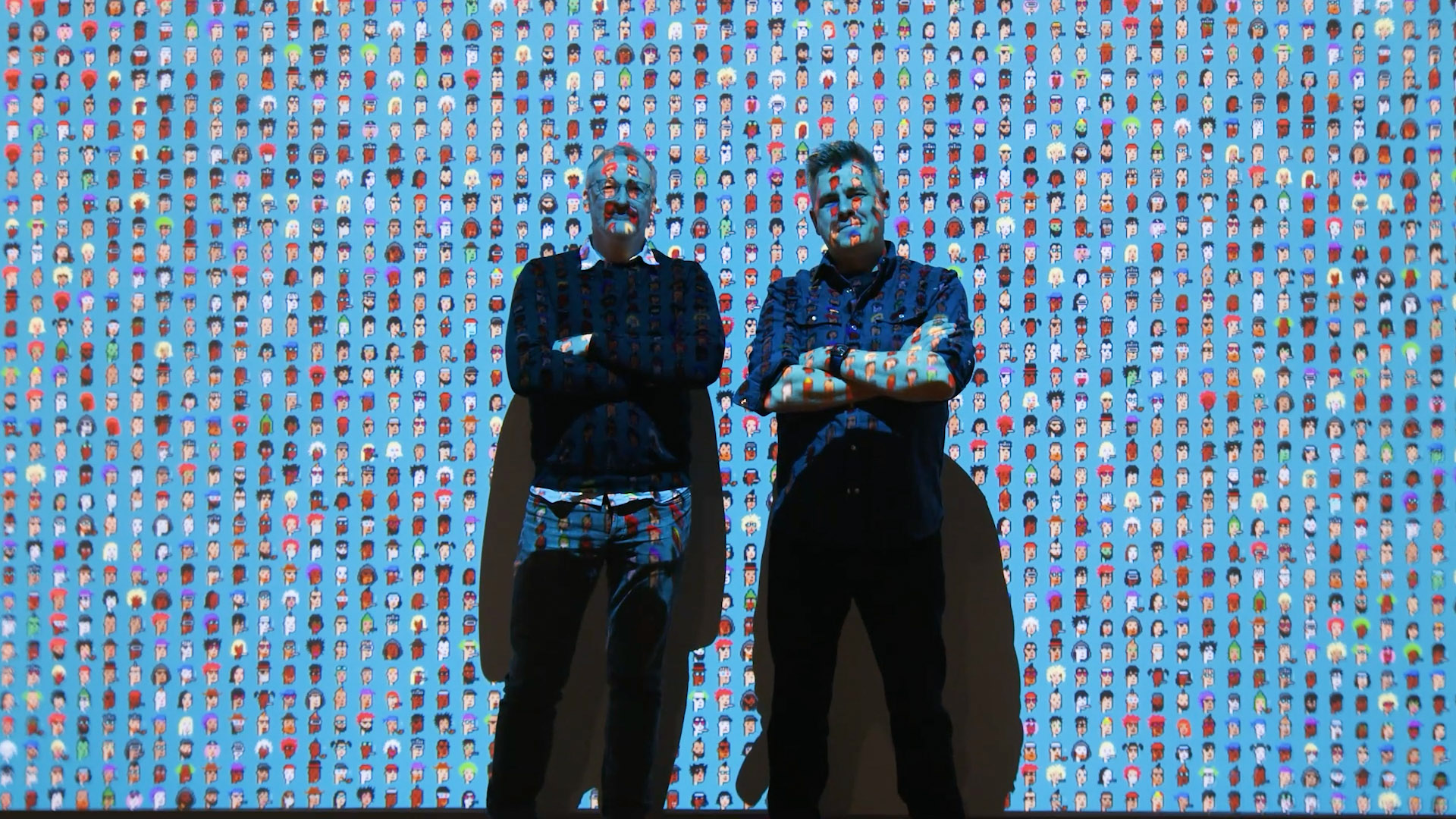

In NODE's opening exhibition, 10,000, artists Matt Hall and John Watkinson put that mission to practice, testing its capabilities. They specifically present CryptoPunks as an animate software-stack whose meaning resides in continuous execution: code running on Ethereum, a built-in marketplace and a community that experiences that heartbeat together.

This means that presenting the collection as a series of images, as most museums have done, would simply be inadequate. Watkinson told me, “We wanted this to be something that's not just frozen in amber. We wanted it to actually be responsive, when you come in to feel like you're part of it. You're in this flow now of a living system.”

Living systems require living institutions. What a living institution like NODE can show us is CryptoPunks in a new light, as we haven’t seen them before, revealing what’s beneath the surface, how the artists see them and what defines the work beyond the images: the code, market and community. Natalie Stone, the show's producer, clarifies: “The most important thing to understand about 10,000 is we're not explaining CryptoPunks, we're creating conditions where you can experience how the collection and the art actually works.”

Code

At the core of how “the art actually works” is the project’s 246 lines of code, displayed with annotations for the tech- and non-tech-friendly alike. Watkinson describes the Punks’ organizing logic the pair wished to communicate: “We think of CryptoPunks in these three big categories: One is the generative nature. Then there's this community element. And the last one is the marketplace.”

The code underlies all three categories, as the show’s curator Amanda Schmitt notes: “There are no CryptoPunks without the code. At the very essence of the work is the code, without which there is no marketplace upon which to trade the pixelized CryptoPunks portraits.”

The code is also most responsible for the “generative nature” of the work, which produced 10,000 individual, yet serial, images, randomly initiating outputs with specific rare traits and attributes. Critically, however, the code isn’t treated as the work or over-glorified; it’s a loop in the system. In an ongoing form of relational aesthetics, what the code produces continues in the hands of the people who claimed, held and traded them.

Community

The exhibition title itself elevates the community. 10,000 represents each Punk holder, highlighting how the artists see that group as central to the work itself. Watkinson told me, “This whole project was really made and shaped by those who came in, claimed them for free, and then started trading. People showed up and shaped the project beyond our initial imagination.”

The community, like the code, is just another interconnected layer in the multi-protocolic stack that CryptoPunks are. Hall told me, “There’s an Ethereum network that powers the technical side of it. But there’s also a network of people who are really into this, interacting via this, have formed some community around it and find some identity in it.” Code may have birthed the images but the project itself continues living through the community.

10,000 is the artist's and NODE’s attempt to recreate the experience of a digital community—with its live data, Discord channels and group chats—in physical form. For Hall, 10,000 will “be a moment where this digital network of people becomes a physical network of people,” adding additional layers to the stack.

Market

The work’s element most curious and most often neglected by other institutions, not surprisingly, is the centrality of Punk’s bespoke market. I mean, money is dirty and gauche; artists must be pure and remain wanting. When museums show CryptoPunks, they stifle the marketplace heartbeat and long-duration behavior that holders actually live with, hiding it away like a nasty secret. Hall and Watkinson prefer what to them feels more honest.

“We didn't want to shy away from talking about transactions in a marketplace…. It's just so inseparable from the project itself.”

Even close watchers may not fully realize what’s special about the marketplace at all. But the artists see it, developed before today’s ubiquitous options, as the gateway to the lived experience of holding a Punk. Watkinson unpacks: “We built this decentralized marketplace. And that's this perpetual motion, zero-fee, continually running system. We think that's really fundamental and really special about CryptoPunks.”

But, of course, the code, community and market are all related. Watkinson shares how “to those who are interested in the Punks community, the drumbeat of the marketplace is just fundamental to their enjoyment of this artwork.” By highlighting the dynamic, networked elements of Punks, NODE is serving a different function than a traditional institution: operational stewardship for living systems, centering their presentation, education and preservation.

Stewardship as Infrastructure

Operational stewardship means showcasing—and in the case of CryptoPunks maintaining—the technical, social and temporal conditions that keep a work executable throughout its intended duration. In the case of Punks and many living works, that’s as long as possible.

Presentation is one key, making a nebulous, disparate system, like CryptoPunks, perceptible and legible in real time requires so much more than a grid of Punks. It means modularity, creativity and the technical expertise that can be almost impossible for cash-starved galleries to acquire.

But NODE’s team of engineers ensured its 12,000-square-foot space was “built around complete modularity with a comprehensive ceiling grid system providing rigging, power, and data points that enable infinite spatial configurations,” according to the foundation.

Basically, if you’ve been to a Bright Moments event, NODE has that distinct feel, except this time in a permanent space, like a Bright Moments meets Beeple Studios.

In addition to presentation, NODE stresses education, favoring playful participation, doing rather than telling. Schmitt details NODE’s approach: “As visitors move through the space, they will learn about different aspects of CryptoPunks: its typology, connection to the blockchain, and the fact that it’s a living piece of software.” This mostly does not include wall text; instead, the exhibition encourages curiosity and activity—press, push, drop, twist, insert—as well as attention.

Schmitt explains, “At NODE, learning happens through experience: through movement, interaction and time spent looking.”

Time spent looking. Here, technology doesn’t equal speed and art doesn’t equal slow. Even one of the most technologically state-of-the-art, digitally native institutions is encouraging thoughtful consumption. It’s fast art asking you to look slowly.

And as you look, you’ll always be noticing something new—a new bid, a new trait combo—which highlights a particular challenge with living systems: preservation as less a battle with an object’s entropy and more the ongoing work of keeping the conditions of emergence intact. It means maintaining the infrastructure and social context that allow the work to continue existing, even beyond the confines of the exhibition dates and space.

Museums excel at stabilizing objects for looking; living art needs institutions that stabilize systems for continuing.

Coexistence and Symbiosis

Yet traditional museums remain essential for holding and preserving culture across generations, connecting today’s urgency to the deep archive from which it grows.

Rather than replacing that function, NODE serves as a complementary model for a burgeoning form of expression that doesn't settle so easily into objecthood, that exists in perpetuity while it runs. It’s not a site to display static art objects nor is it a venue for one-off relational experiences; it’s a durational, self-updating institution for living artworks that anchors ongoing execution.

That’s why modularity matters, both through internal flexibility and externally: NODE can exist as its own organism or it can graft onto older ones. As founders Becky Kleiner and Micky Malka told me, “It’s not only that we hope to see more NODE locations around the world; honestly, we hope that museums take this and say, ‘I'm going to build a NODE inside my museum,’ and use our technology and our best practices.”

Life evolves both by slow mutation and sudden symbiosis. NODE is one such symbiotic leap, merging the stewardship of a museum with the operational infrastructure of Silicon Valley, producing a new institutional species.

------

Special thanks to Becky Kleiner, Micky Malka, Matt Hall, John Watkinson, Amanda Schmitt and Natalie Stone for their contributions via interview.

Peter Bauman (Monk Antony) is Le Random's editor in chief.