Larva Labs on Computation’s Strangeness

.jpg)

Larva Labs on Computation’s Strangeness

Creative technologists Matt Hall and John Watkinson, known as Larva Labs, speak with Peter Bauman (Monk Antony) ahead of the release of Quine, the final Art Blocks Curated project. They discuss elevating code to artwork itself, the deep strangeness of computation from Gödel to Hofstadter, and how Quine stands as an ode to classical programming in the age of AI.

Peter Bauman: Quine is the final Art Blocks Curated project. Can you talk about how the work plays with that legacy and the decision to foreground code?

John Watkinson: After Erick [Calderon] approached us, we didn't want to say yes right away because we felt almost a burden to get it right. We didn’t want to end this storied series with a whimper. We pushed them off for a couple of weeks while we thought about what we could do that felt fitting to wrap this up.

Art Blocks is a very generalized platform in order to allow artists to do whatever they want. You really have this blank canvas. Matt and I eventually arrived at, "What's cool and unique about Art Blocks?” I think Autoglyphs was even an inspiration for Art Blocks, stressing the separation of the artist from the outputs, that the artist just makes the code.

Well, it'd be nice to celebrate the code, to make it about the code—somehow push that up front. Then we thought, “It'd be cool, rather than just simply printing code somewhere in the artwork, if that code somehow meant something.”

It’s not just that there's a copy of the code sitting in the contract; no, you can actually run that code. That code matters.

Then we dug through our nerdy past in computer science and thought of quines, which are computer programs whose output is its own program listing. It's a tricky problem to think about how you actually make a quine where it's completely self-contained and it can run and generate its output. In every language you almost have to take a different approach. As soon as we had that idea, that's when it clicked for us:

This now feels like a Larva Labs project where we have this constraint that's going to dictate how the rest of the project goes.

This tricky quine structure is going to force our hand in decisions, lead us down certain paths and compel us to a certain minimalism. Then it also just felt right for Art Blocks to celebrate the code in the last chapter because it’s all about expressing yourself with code and kind of only code.

We were recently at the Toledo show, which had several Art Blocks projects: Fidenza and Ringers. They have prints on the wall, which look nice, but you don't get that relationship, if you're just a casual museum viewer, of what's different about this compared to the other work on view.

Maybe we can push that new relationship a little closer to the viewer. It might at least invite them to think about it a bit or lead them to find out more because it's in the foreground.

Matt Hall: We're trying to reveal the workings of this and make it at least a little bit understandable because knowing a little bit of how it works is why we love it. If you're not a programmer and you come to a digital art show, you look at a screen, and you just have no idea what the process is. It's a very different experience than looking at a painting, where even if you're not an artist, you know what you're looking at. With digital art, it's so difficult. What we're trying to do is put constraints on it that reveal a little bit of how it works. Then in that, hopefully, you understand and enjoy it a little more in the way that we do.

Peter Bauman: You mentioned Autoglyphs. How do you see Quine connecting to that earlier project? Do you see any opposition or tension in that relationship—Glyphs as outward and Quine as inward—or is Quine more of an extension?

John Watkinson: They're both certainly exploring similar themes. Most Art Blocks projects have a generator that is published and responsible for creating an image.

But our generator doesn't make an image. It actually just makes the code.

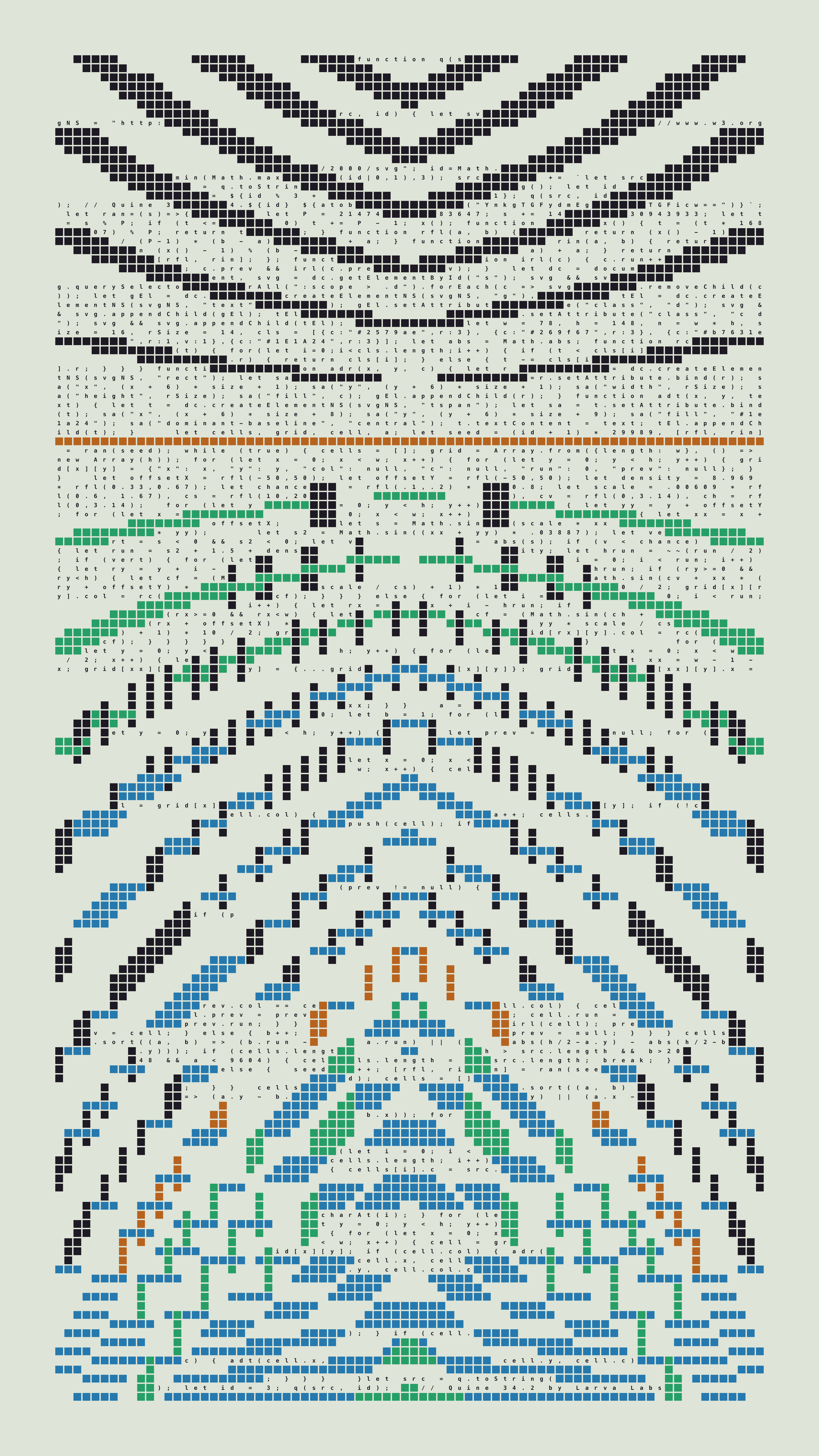

Our code is basically piecing together bits of other code and setting parameter values and then its output is just that source code. That code is what gets run to actually generate an image. Then directly in that output is that code again.

We've gone a little meta here, where this is a generator of generators. Each output is really a little generator. Some are so-called perfect quines, where it's just a generator of itself: if you run that code, you just get the same result. But others have this loop. Then we even have a very small number, the pseudo-quines, where they actually don't ever come back around. They just generate variation.

That's much closer to just being its own little generative art project.

If you look at the images, the code you see is real text. You can actually highlight it. So you can even select all of it and copy it. Then you can use our quining tool to paste and run the code. When you do that, it makes the output. You can repeat that process and if I do this enough, you’ll loop back to the first iteration.

It's fairly accessible. Someone might even be like, “I'm going to change this code. I'm going to mess with these values and try to run that.” It invites that interaction, which is a lot harder to do than for most other Art Blocks projects.

Peter Bauman: You're asking the audience to place the code on the same level as the output itself, as a work of art. That also asks them to think about the historical lineage of this work, not only in art historical terms but also in computer science history terms. What are you saying about the difference between art and science?

And can you talk about how the project is an ode to the canonical history of programming, including Gödel’s incompleteness, Turing’s computability, and maybe most directly cybernetics and Hofstadter’s idea of “strange loops”?

Matt Hall: We both started programming at a young age and your first experiences with that are just trying to get the machine to do what you want it to do. It's hard because you're learning the language at the same time. You get a little better and then you feel like, “Okay, this is programming. I've got it.”

Hofstadter's book was part of this but also studying the theory part of computer science revealed this whole other world of how strange computation really is—how universal and fundamental.

Some people, like Stephen Wolfram, believe it is fundamental and that physics is driven by that at this lower level. It feels right in the same way Conway's Game of Life, which is a simple rule system in a way, was proven to be a universal computer. All these little rule systems can produce infinite worlds, which was such a mind explosion when I was younger.

John Watkinson: We didn't think of ourselves as artists making CryptoPunks. We almost had it pitched back to us by the art and collector community. The reason we didn't was because we were mostly coming at this stuff from a technical point of view. We were trying to solve technical problems, trying to make things work within these constraints and that was the case for Autoglyphs as well.

But then we realized that this science-focused method of expression is just as valid as anything else.

We realized there are collectors out there who really care and know about this stuff. We've learned to lean into this. We come from this science-tech background. We love this stuff and there are other people out there now, too. So we're quite comfortable being nerdy about what we do and how we talk about it.

Quine maybe is setting a new bar for that because it's really nerdy.

Matt and I both read Hofstadter's book, Gödel, Escher, Bach, when we were teenagers, independently.

That strange loop stuff, that really stuck with us.

Then later in college, learning Gödel's Incompleteness Theorem, I would say that's maybe my favorite proof of anything. That's one of the most astonishing results that science has ever produced: this idea that we can prove that logic systems can never be complete. That all came at a time when there was a real philosophical belief that we could mechanize everything.

There was an idea that eventually we wouldn’t need mathematicians, that we could just have these mechanical logic systems that could prove anything you want. But Gödel’s result put a wrench in that. It had big reverberations on the philosophical space. I think we find ourselves in a similar time right now where people have this almost fanatical belief in AI systems. I feel like all these themes are ripe for rediscovery.

Peter Bauman: Another key reference for this work is Karl Sims because Quine also has this relationship to self-replication and artificial life.

John Watkinson: What we're doing is self-reference, where the code is this functional thing that makes this shape that we see on the screen now, but it also is data that gets copied and passed on to its next iteration. That's close to Karl Sims's work with reproduction and his geometric Evolved Virtual Creatures.

They have this behavior and structure that's represented by a DNA-like program, which gets replicated and mutated. That's what Matt was talking about, where you discover these worlds of what you can do with code.

It’s closer to this phenotype-genotype thing that he had going on. Sims had code that defined the body structure but then also intertwined the behavior. It was in this representation that allowed for copying and mutation. That got us thinking about how we want that, too. We want these different forms. That led us to this idea of these five different engines (Shape, Glyph, Force, Ribbon, Lattice). They’re almost like one type of creature, each with a certain look to it.

Matt Hall: I hadn't thought of this before but a big difference between Quine and Sims is that a lot of genetic algorithms have a fitness function. In Sims's case, it was this physics world simulator. I thought we didn't have a fitness function but just realized, “Oh, wait, no, we are the fitness function. We perform the function, our aesthetics.”

There's a direct analogy there because we had engines that didn't survive, that didn’t make the cut.

Peter Bauman: You mentioned earlier that it only felt like a Lava Labs project when you discovered your constraint. How did reframing scientific constraints in this artistic context also invite the viewer to think about them differently?

Matt Hall: We just want constraints in order to work. It was almost daunting initially with our platform being this empty canvas and you can do anything you want. And on Art Blocks, there'd been so much great stuff done already, especially from a visual perspective.

We needed to bring Art Blocks into our world a little bit—make it have some conceptual limitations that felt interesting to us. That then forced us to constrain the visual output as well.

What that gets for the viewer is a view into this strangeness of what we're all looking at here, which is what we love about it.

John Watkinson: We do like minimalism and stripping an idea down to its minimal core so that it is put forth as strongly as possible. We decided, like pixel art again, to have each output composed of just these fairly simple cells. We felt if we had a more complex visual look, then it would just be hiding the concept.

Matt and I always have a theory, too, that if you have to add a bunch of stuff, if you have to decorate your idea with a bunch of things, then maybe the idea isn't strong enough to stand on its own. We like the ideas that feel strong enough where you can strip everything down and just say, “This is what it is,” and then put it forth in a really minimal way.

Once we got onto the idea, the constraints started to reveal themselves naturally. We wanted the artwork to look like a code listing a little bit. This is a 78-column code listing, which is pretty close to the eighty columns that would be standard in a terminal text editor environment. We didn't want it to be so dense that you don't even see the code. There was some constraint there where we felt it had to be enough cells where we could fit the code and we could still have some variants in design.

Those are the constraints that we like to operate on. Once we have the idea, the answers start to flow a little. And we feel like we can back up those answers and feel good about them because it's all coming from the original concept.

Peter Bauman: How did the constraints specifically impact visual elements like color palette?

Matt Hall: With Autoglyphs, there were very few dimensions of freedom there. It was black and white. It was just a symbol set and placement. With Punks, we didn't think about color that much. It was just whatever we needed: this hat needs to be orange or whatever.

We wanted to be more intentional about the colors with this one. We certainly researched previous Art Blocks projects to see what felt like it worked for us. What we were trying to achieve was the idea that there is variation, but the whole set feels cohesive. It's not like there's an overall color theme to the whole set but there are surprises and variations within that.

John Watkinson: We haven't really worked with color in the abstract before, where we could choose any colors. We actually had randomly generated colors under constraints that we played with for months. Then we started curating that, where certain combinations somehow felt right. We started to build up this shortlist of colors and color combinations that made sense. Then eventually, we did an exercise of distilling it down. There are ten colors present in the project, in total, as well as black and white. Then we've combined them in different ratios.

Peter Bauman: You mentioned earlier that computation is quite strange. Quine ultimately seems to be this investigation of computation, asking the audience to think more deeply, even reflect, on computation.

In that spirit, we also talked about how Quine foregrounds the canonical Turing view of code: a closed, rule-based program that reproduces itself. With AI and even quantum computation challenging computation’s “Turing orthodoxy,” do you see Quine as reaffirming that tradition or as an ode in a moment of transition?

John Watkinson: I even think part of Erick's decision to end the Curated series was because he feels we're entering a new domain. They're getting increased submissions from artists that lean heavily on AI, where you just get the sense that it's going to change the nature of how people make things. If that underlying medium changes, then it will affect the outputs as well.

What we've done is definitely very much an ode to the old method, where this is very handmade, especially because we have to compress this. The code has to be very small; it has to be very tightly designed so that this whole quine structure works and fits everything.

This is very much a handmade, old-fashioned style, as opposed to just getting the vibes on.

We don't know exactly what to make of all that. I don't think creativity itself is under threat. I've never had that feeling that artists will be disintermediated by AI creativity.

I think Matt agrees that it's more about tools and what we can do. Even as Matt and I have been data and software developers for thirty years, we still are changing how we're programming because we have access to these tools. It allows us to work with libraries or systems or languages that we're not familiar with.

We can get up to speed quicker. We can dip our toes into things that we don't have a ton of experience in without a huge upfront heavy load.

Matt Hall: We’re honoring simple rule systems that produce complex behavior. AI is probably the extreme opposite of that spectrum: the most complicated. It's so complicated that people are ascribing otherness to it. But it's still a computer running it, guys.

It's interesting also the Incompleteness Theorem and how that bummed out a whole generation of theoreticians and mathematicians who were trying to create this whole thing. I suspect that AI is still bound by those limitations. No matter how complicated the rule system gets, there are probably still these overall limitations to it.

Peter Bauman: Finally, can you talk about the decision to donate a portion of sales to Node and what their stewardship means for the Punks collection?

Matt Hall: We've been working with the team at Node on a CryptoPunks show, which has been announced for January. It's a pretty substantial endeavor and it's offered us the chance to explore some of what we've been talking about in a way that we haven't been able to before in a museum or a gallery space. We just really appreciate what they're doing and their mission and wanted to support it. It's an organization, with people like Becky and Micky, that really understands what's interesting about this stuff and wants to support it.

John Watkinson: We're quite thrilled that this long-term-thinking nonprofit now controls the CryptoPunks IP. But their overall mission is to be a supporter and booster of digital art in general.

The idea of putting a physical museum space right in the heart of Silicon Valley? That's just a really cool, maverick idea.

We heard right away from some people who come from a pure art background who said, “Why would you put a museum there rather than in a major city center or something?” But it made perfect sense to us.

It's like, let's go there to where the heart of all this computer science stuff is happening.

We're just happy to play our role in supporting it.

-----

Matt Hall and John Watkinson are creative technologists who have worked broadly with software. They are best known for co-founding Larva Labs, where they created CryptoPunks and Autoglyphs. They also create large-scale web infrastructure, genomics analysis software (Watkinson has a Ph.D.) and 8-bit roleplaying games. Their work can be found in museums worldwide, including Centre Pompidou, LACMA and ICA Miami.

Peter Bauman (Monk Antony) is Le Random's editor in chief.