Lu Yang on Art as the Perfect Cloak

Lu Yang on Art as the Perfect Cloak

Lu Yang’s DOKU! DOKU! DOKU!: samsara.exe at Amant in New York, on view through February 15, lands alongside Museum of the Moving Image's presentation of Lu Yang: The Great Adventure of Material World (2019–20), on view through March 22.

The artist speaks with Peter Bauman (Monk Antony) about solitude as an absolute truth, art as the perfect interdisciplinary cloak, and the illusory boundary between body, avatar, dream and “reality.”

Peter Bauman: DOKU—your avatar, whose name means “solitude”—comes from the Japanese Buddhist phrase dokusho dokushi (“We are born alone and we die alone”). Solitude in the West is often viewed negatively and called things like a "loneliness epidemic.” Is that how you see it? What’s the difference between loneliness and solitude? What’s the difference between how they’re viewed in the West compared to Japan and China?

Lu Yang: The name DOKU originates from the Buddhist scripture, the Infinite Life Sutra (Fo Shuo Wu Liang Shou Jing), specifically the passage: "People in the world, amidst love and desire, are born alone and die alone, go alone and come alone." I adopted the Japanese pronunciation "DOKU" (for "solitude") because of its phonetic strength and ease of dissemination.

To me, this phrase is not a pessimistic sentiment but an absolute truth. If you observe the nature of existence, there is not a single life form that does not follow this pattern of arriving and departing alone.

I believe our current social systems have heavily stigmatized the concept of loneliness because a solitary existence does not align with the developmental logic of the "system." Our societal structure is built on connection, consumption and collective interaction; it requires individuals to constantly validate their worth through relationships to keep the machine running. Therefore, an individual who can fully abide in solitude is often viewed as an anomaly or a failure.

However, the "solitude" I speak of is not about shutting oneself at home, scrolling through phones, playing video games or engaging in virtual socializing to escape reality—that is merely another form of distraction.

The solitude I refer to leans more towards a deep state of "internal observation" or Vipassana. Throughout history, great philosophers and thinkers have excavated their intrinsic wisdom through this very path. Just as the Buddha attained enlightenment sitting alone under the Bodhi tree, this internal awakening cannot be achieved amidst the noise of a crowd.

This aligns perfectly with Carl Jung’s concept of "individuation." To integrate one's shadow and realize the wholeness of the Self is a journey that must be faced alone. No one else can perform this psychological process for you. Ultimately, it depends on the choice you make: to live as someone who conforms to the social structure or to take the road less traveled.

In China, and indeed within the current global context, the mainstream worldview still tends to perceive loneliness as a symbol of a tragic fate. However, what the majority often fails to realize is the immense joy and freedom that lies behind this solitude.

As Arthur Schopenhauer suggested, a man can be himself only so long as he is alone, and if he does not love solitude, he will not love freedom. For those who can find self-sufficiency in their spiritual world, solitude is not a deficit but a supreme enjoyment; it is the state we must embrace to attain this absolute freedom.

Peter Bauman: You mentioned the spiritual world. Across your projects, it seems like the virtual, spiritual and physical bleed into one another. How do these three domains interact in your life and practice?

Lu Yang: To be honest, since I was a child, I have been bewildered by the rigid categorization of disciplines in our world. Since I have arrived in this existence, why must I confine myself to a single, subdivided field and strive to become a specialist only in that narrow lane? This fragmentation feels unnatural to me.

My logic in creation is simple: if I want to explore the essence of a question, I must approach it from every possible angle, whether it be scientific, religious, or artistic.

Consequently, I often produce works that might appear to others as a chaotic "mashup." But this is precisely how I comprehend the world.

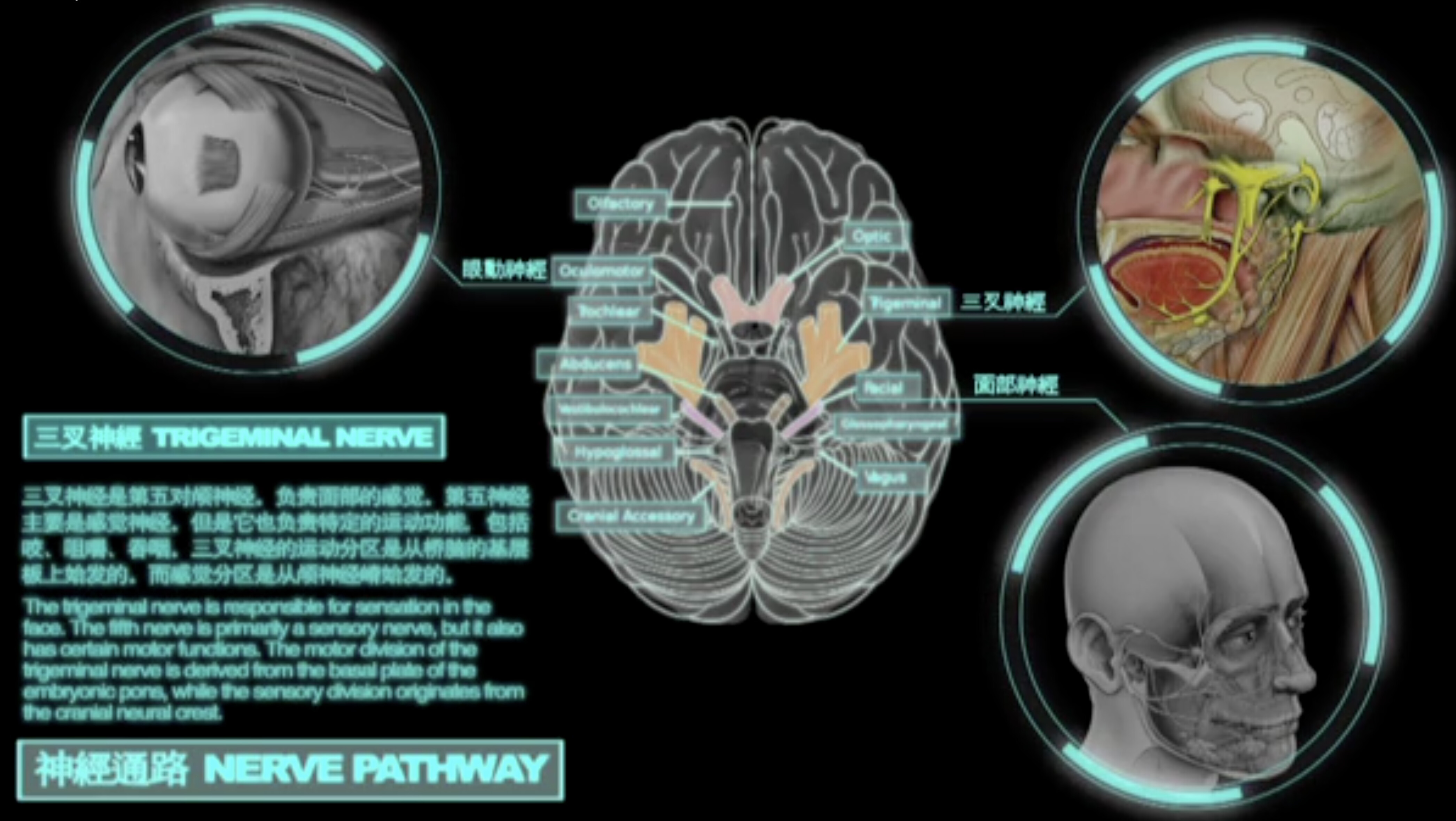

Take my 2011 work Wrathful King Kong Core as an example. I wanted to investigate the mechanism of "rage." To do so, I simultaneously introduced research from two dimensions: the spiritual dimension, specifically the Wrathful Deities in Tibetan Buddhism, and the neuroscientific dimension, specifically the biological pathways in the brain that process emotion.

In my mind, these two are not contradictory; they are merely different languages describing the same truth. In my mind, the walls that are supposed to separate these domains have never existed. On the contrary, I find myself confused by the societal cognitive systems that are so obsessed with erecting these barriers. Therefore, becoming an artist was never my childhood dream.

I chose this profession simply because I discovered that "art" is the perfect cloak. Once I put on this layer, I can explore any field—be it neuroscience, religion, or technology—under the guise of "creation."

It is a highly "cost-effective" strategic positioning. It allows me to find a "blurred zone" within this strictly subdivided world, a space where I can move freely without obstruction.

Peter Bauman: How does resisting those categorizations work in practice? How does our physical individuality translate into virtual spaces? To what extent does it matter, for you, whether an experience is lived “in person” IRL or inside a digital simulation?

Lu Yang: For me, there is no fundamental difference between so-called "physical individuality" and a "virtual avatar."

While the sensory feedback (haptics) may differ between these two dimensions, at the level of consciousness, the boundary is illusory.

To answer this, I must draw upon Buddhist philosophy, specifically the perspectives found in the Lankavatara Sutra and Mipham Rinpoche's The Debate between Waking and Dreaming.

First, according to the Lankavatara Sutra and the concept of "Mind-Only" (Citta-matra), the external physical world is no more "real" than the images projected by our consciousness. All experiences—whether touching a physical cup or interacting with a digital object in a simulation—are essentially data and signals processed by the Alaya-vijnana (Storehouse Consciousness).

I often have profound experiences within dreams where my sensory perception remains acute. In a dream, I can grasp an object and feel the same resistance and texture as in the physical world; I can create music and hear distinct melodies; I experience acute pain and extreme joy.

Whether I am lucidly aware that I am dreaming at that moment or lost in the narrative, the validity of the experience in that instant is indistinguishable from the physical world.

As revealed in the dialectics of The Debate between Waking and Dreaming, if the experience within a dream is real to the dreamer in that moment, then by extension, our so-called "physical reality" might simply be a more stable, longer-lasting "Great Dream."

With the advent of AI, we are rapidly descending into a situation where distinguishing between the real and the virtual is becoming impossible. Generative AI is creating images and interactions that bypass our reality filters. In this technological context, I believe that obsessively debating "what is real vs. what is fake" is no longer important.

For me, the ultimate task is not to judge the superiority of an experience lived "in person" versus inside a simulation. Rather, it is to seek what the Shurangama Sutra calls the "True Mind" (or Intrinsic Awareness).

Whether I am inhabiting a physical body, a digital simulation, or a dream state, who is the "observer" that is aware of all these changes? Who is the unmoving witness? That is the only question that matters.

Once you find this "True Mind," the specific shell or dimension in which the experience occurs becomes irrelevant.

Peter Bauman: What role does spirituality play in your practice day to day? Is there any difference between your spiritual life and your artistic work?

Lu Yang: This is a very honest answer: I know myself very well. I know what I deeply love but I also know how lazy I can be as a human being.

If I were to treat spiritual practice merely as a hobby, given the natural inertia of human nature, I might never dive deep enough. Therefore, I adopted a strategy:

I use my artistic career as a vessel to forcibly "bind" my most obsessed philosophical systems with my daily work.

For me, art is not just about creation; it is a mechanism I use to counter my own inertia. Establishing this professional path transformed studying obscure scriptures and complex philosophical concepts from an "optional interest" into a "mandatory professional imperative." This means that, regardless of my mood, I am compelled to spend a significant amount of time every day immersed in these ideas. In this process—whether through active, deep contemplation or the passive, subconscious absorption that happens during production—these philosophies are constantly reshaping my mind.

Consequently, there is no boundary between my spiritual life and my artistic work.

They are effectively one and the same field. I don't see the necessity for such a division. History shows us that for many great predecessors, the pursuit of truth, their way of life, and their creative expression were always an indivisible whole.

I simply use this "professional binding" to ensure that this inward exploration is not an ethereal vision but becomes a concrete reality that I must practice every single day.

Peter Bauman: Can you discuss how you see world-building and your philosophy of creating worlds?

Lu Yang: First, I will address my limitations. As a human being, from the moment I "logged in" to this reality, I have been bound by the underlying rules of this world. I am merely a part of this massive system; I cannot suddenly transform into a "bug" or a "glitch" to transcend the logic of this dimension.

.jpg)

From a macro perspective, all the "world-building" I do is essentially a reshaping within the framework of human cognition. For example, I cannot create a truly alien ecosystem that completely defies earthly logic because I have never experienced such possibilities nor can I verify them.

All my imagination is, in fact, a projection based on the "reality game" I inhabit.

However, this does not diminish the fascination of world-building itself. Whether I am creating video games or working with game engines for real-time rendering, what captivates me most is how easily this process induces a "flow state." It is like a child building a sandcastle on the beach—I become completely immersed in it.

In that moment of creation, so-called "objective meaning," "grand narratives," or "philosophical purposes" all fade away. What remains is pure immersion, the joy of absolute focus within a finite sandbox.

Peter Bauman: What distinguishes a world from a mere setting or backdrop?

Lu Yang: In the wisdom of the Shurangama Sutra, all material appearances are illusory, yet we can "use the illusion to cultivate the truth" (借假修真). Every scene I build, every iteration of DOKU, acts as "Upaya" (Skillful Means). Their sole purpose is to serve as a visual pathway, guiding the audience to touch an essence that is beyond words.

What distinguishes a "world" from a mere "setting"? For me, if an environment is just a collection of decorative visuals, it is merely a backdrop.

But if an environment possesses an internal logic (such as karma or samsara) and functions as a lens through which the audience can glimpse the underlying reality of existence, then it is a living "world."

Whether it consists of virtual pixels or physical installations, as long as it reflects the Essence, it is valid and complete.

Peter Bauman: How do you think about your audience (viewers and players) as co-creators of these worlds? By inhabiting worlds, how do they help bring them into being?

Lu Yang: I must be honest; during the actual creative process, I rarely think about the audience. For me, creation is a form of practice (sadhana), a cultivation, and even a deep self-healing. What I need to obtain—the internal order and joy—is already fully achieved during the process itself.

However, once the work is completed, it is thrown into reality to establish and sustain my professional persona as an "artist." At this stage, I believe in resonance. The work is what it is and naturally attracts specific audiences who slice off their own pieces of understanding from it. The feedback I receive from reality does indeed seep into me, becoming one of the reasons I firmly continue to create.

Regarding the concept of "co-creators," I prefer to explain it through the lens of "Collective Karma" (Gongye).

If we view this world as a massive online game, then my audience and I are simply players who happened to "log in" during the same timeframe.

We encounter each other because, on some level, we share a collective karma. This mutual achievement and mutual influence are simply the underlying rules of this game world.

Furthermore, my work does not descend from the void. It is a transformation of the wisdom I have absorbed from the many "finger-pointers" (masters of truth) who came before me. My sincere aspiration is that any audience member who encounters my work receives positive inspiration. In this sense, they are more than co-creators, an integral link in this chain of wisdom transmission.

Peter Bauman: You’ve spoken about the creator and the created collapsing into one another. When you design a world, do you in some sense become that world? And are these environments complex self-portraits for others to temporarily inhabit?

Lu Yang: When I see this question, one sentence comes to mind: "Your thoughts are not you."

Although these worlds stem from my thinking, since thoughts are not the "Self," these works cannot be called "self-portraits." At most, they are "slices" or "specimens" of my mental activity.

I am not the environment. I am the "Observer" watching the rise and fall of these thoughts.

When I invite the audience to inhabit these worlds, I am inviting them to tour my "Mind Stream," not to meet the "Me" behind it.

Peter Bauman: Are there more “worlds,” in your view, than the earthly one our waking consciousness inhabits? How do your works navigate between these different planes of reality or unreality?

Lu Yang: Absolutely, I believe that the "earthly world" we perceive while awake is merely one slice of countless existing realities.

For me, the definition of a "world" is broad and multidimensional. When you are deeply engrossed in a book or immersed in a film, you have effectively entered another independently functioning world.

Similarly, during sleep, we traverse various layers of dream worlds. Even on a psychological level, as Carl Jung described, our conscious mind, the personal unconscious, and the collective unconscious—each layer is a vast, profound universe in itself.

My works, such as those based on the Buddhist concept of the "Six Realms of Samsara," are attempts to visualize these landscapes across different dimensions. These worlds do not exist as isolated parallel lines; rather, they are intricately intertwined.

Reality and fiction, waking and dreaming, the conscious and the unconscious—they are constantly bleeding into one another. My work is to navigate through these interlaced interfaces, attempting to capture the moments where they overlap.

Peter Bauman: You mentioned the “Six Realms of Samsara”—heaven, asura, human, animal, hungry ghost and hell. The Great Adventure of Material World, on view at MoMI through March 22, 2026, draws on this framework, challenging our attachment to desire. Why is this work from 2019–20 still perhaps even more relevant today as we near 2026?

Lu Yang: The reason this work feels more relevant today than ever is that it explores a core mechanism of the universe: the cycle of "Formation, Existence, Destruction and Emptiness" (成住坏空). This is an eternal natural law, and right now, it is playing out violently before our eyes.

The physical container we inhabit (the "Material World") must inevitably pass through these four stages. While this cycle has always occurred throughout history, in the past, we could only look back at disasters and collapses through dry history textbooks, which felt distant and abstract.

Today, however, with unprecedented freedom of communication and advanced recording methods, the process of this cycle—especially the stage of "Destruction"—has become incredibly vivid and visceral.

Through our screens, we are witnessing the turbulence and crumbling of systems in real-time, every single day. From the perspective of Buddhist cosmology, whether we are facing "Great Kalpas" or "Small Kalpas," the wheel of time is turning along its destined track.

While our material technology is exploding, we can simultaneously sense the "Disappearance of Wisdom." This contrast makes our current situation feel even more absurd and urgent.

It is not that this work predicted anything back then; rather, it reveals an inevitability. Whether in 2019, 2026, or the future, as long as we inhabit this "Material World," we cannot escape the constraints of these natural rules. The current state of the world has simply made this brutal truth more visible than ever before.

Peter Bauman: DOKU the Self (2022) from your Venice Biennale show and now at Amant, circles around the “pseudo-concept” of the self and ideas of anatman, or non-self. How is the work asking the audience to rethink the self during this age of destruction as “real life” blurs with the digital?

Lu Yang: As the inaugural work of the DOKU film series, DOKU the Self undertakes the most fundamental and difficult task: to begin "peeling away" the self from its very core.

The inspiration for this piece comes directly from a wondrous flight experience I had. I intensely experienced a state akin to the "Overview Effect." High in the air, my usual perspective suddenly fractured and reorganized; it was as if I were detached from my physical body and the gravity of the mundane world.

That vibration completely shifted the coordinate system through which I view the world.

It was to recreate and sustain this shift in perspective through art that I launched the DOKU project. I digitized my physical body not merely to create an avatar but to create distance. When I look at that digital being on the screen—who has my face but is not me—I am effectively forcing myself (and the audience) into that "Overview" perspective:

If that digital shell is "Lu Yang," then who is the "I" observing it?

Through this bifurcation of the material and the digital, the work forcibly shatters our singular identification with the "Self." It is not only the genesis of the DOKU universe but also my first attempt to verify the ancient truth of anatman (non-self) through technological means.

Peter Bauman: Then in DOKU The Flow (2024), also at Amant, DOKU boards the Desire, a cruise ship dedicated to hunger, wealth, sleep, fame and sensuality. Buddhism and other religions have long histories of critiquing material temptation. How do you think about “digital” temptations and cravings specific to networked, screen-based life?

Lu Yang: The prototype for "The Desire" ship comes from a real experience I had in Miami. I remember standing on the street and seeing a massive "building" moving in the distance; only upon closer inspection did I realize it was a super cruise ship. The subsequent voyage shocked me—it revealed what colossal machinery humans have created solely to satisfy desire.

On board, I felt exactly like a character in The Sims: mindless. When my "hunger" or "fun" stats dropped, I simply went to a designated task point to replenish them until the bars turned green again. It was a surreal, heaven-like efficiency.

However, the "paradise" on the cruise had physical barriers (like expensive internet that cut off signals), whereas the "digital desires" of real life are cheap, instant and pervasive.

There was a time when I was pressured by peers, who insisted that as a contemporary artist I had to be active on social media for the sake of my career. I tried it and it was catastrophic.

The anxiety of constantly being in a context of "being compared" and "being seen"—drafting captions, checking notifications—nearly destroyed my creativity. It is a high-efficiency dopamine trap that is incredibly hard to quit. But I eventually chose to opt out. I have now almost completely cut off social media; I rarely check WeChat or feeds.

I discovered a profound truth: when you disappear, no one actually cares because people are ultimately only looking at themselves.

Realizing this brought me unprecedented freedom. As for the screen, watching the occasional puppy video on Instagram is enough for me.

Peter Bauman: In addition to Self and Flow, there is DOKU the Creator (2025) and the upcoming fourth installment, DOKU the Illusion. What can you tell us about it?

Lu Yang: I am currently working on DOKU the Illusion, which is scheduled to be completed in the first half of 2026.

Interestingly, this upcoming fourth film is deeply connected to the very questions you asked at the beginning of this interview—specifically regarding the boundaries between the virtual and the physical and the dialectics of waking and dreaming.

If the previous films explored "Self" and "Desire," this one will directly confront the nature of "Illusion"—investigating whether what we perceive as reality is merely a more persistent dream.

Peter Bauman: You presented new work at Art Basel Miami Beach 2025’s Zero 10 with UBS Art Gallery. How did that work extend or complicate the DOKU universe?

Lu Yang: We constructed a field that balanced movement and stillness. The booth presented a video work of DOKU dancing in "Heaven," while the gallery space displayed static lightbox works.

Both are integral parts of the DOKU universe. If my films are the flowing macro-narratives, then this exhibition served as a "visual development" extracted from that torrent. The dance video captured the rhythm and energy of DOKU within the cycle of Samsara, while the light boxes crystallized those fleeting, climactic moments into an almost "iconic," eternal existence.

These are not separate entities outside the films but extensions of the DOKU worldview across different media. This combination of the dynamic and the static allowed the audience to both watch a story and to gaze upon slices of the DOKU universe in a way that felt more sculptural and ritualistic.

Peter Bauman: What’s the status of your NFT series DOKU the Creator–Concept Void? Why did you choose to explore NFTs? How does this iteration fit into your broader exploration of creation, emptiness, and authorship inside the DOKU system?

Lu Yang: In the phase of DOKU the Creator, DOKU undergoes a fundamental identity shift: he is no longer just a "character" or "avatar" controlled by me but evolves into a "Creator" with his own agency.

Since DOKU is a native digital being, the work he "creates" is naturally purely digital. This raises a very practical question:

How do we authenticate "digital works created by a digital human"? In this context, a traditional physical paper certificate of authenticity would feel absurd and anachronistic.

Therefore, my choice to explore NFTs was not about chasing market trends but an ontological necessity. For digital works made by a digital entity, there is no better form of certification than an NFT. It is the native contract of the digital realm. Currently, it is the only and best way to establish DOKU's identity as an independent author and to provide an immutable "digital birth certificate" for his creations.

------

Lu Yang is a contemporary interdisciplinary artist whose multimedia practice is deeply influenced by Buddhist philosophy, exploring themes of self, life, technology, and spirituality.

Peter Bauman (Monk Antony) is Le Random's editor in chief.