Holly Herndon & Mat Dryhurst on Artificial Psychedelia

Holly Herndon & Mat Dryhurst on Artificial Psychedelia

Artist duo Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst spoke with Peter Bauman (Monk Antony) about their major new work Starmirror at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, on view until January 18, 2026. They discuss the work within the larger context of protocols as worlds, AI’s impact on public space, and the blurring line between artists and scientists.

Peter Bauman: Let’s begin with your current show. Can you talk about how Starmirror extends your two-decade investigation of voices and machines, including 2024’s The Call?

Holly Herndon: Starmirror is chapter two in the series, the German edition. With the UK edition, The Call, we were looking at the UK choral canon and mixing that with Sacred Harp music for the songbook that we wrote for the choirs to sing.

For this edition, we were looking at the German repertoire, but I think we've all celebrated German classical music to death, so we didn't want to dive into that period. We decided to go back even earlier to medieval Germany and found Hildegard von Bingen, who's actually having a bit of an art moment right now, which is really funny. There are all these things that are inspired by her.

There's this joke that the first Renaissance man was a medieval woman and it was Hildegard von Bingen.

She was a wild mystic. These visions would come to her and then she would write them down as poetry, as music, as herbal medicinal recipes. She really was dabbling in all of the arts and sciences of the time.

So we made a model based on her canon. Then added some things that, since we're using models, we might as well use models for what they're good for.

We imagined if polyphony had been invented while she was alive so we added some polyphony to her style and used that as a springboard to create the songbook. We've been using that to host sessions for call-and-response singing in the exhibition space.

The UK version was really a tour on the road where we went out and recorded all the choirs. I packed my mom and our, at the time, one-year-old into the back of a car and drove around the UK on the other side of the road, recording choirs all over the place.

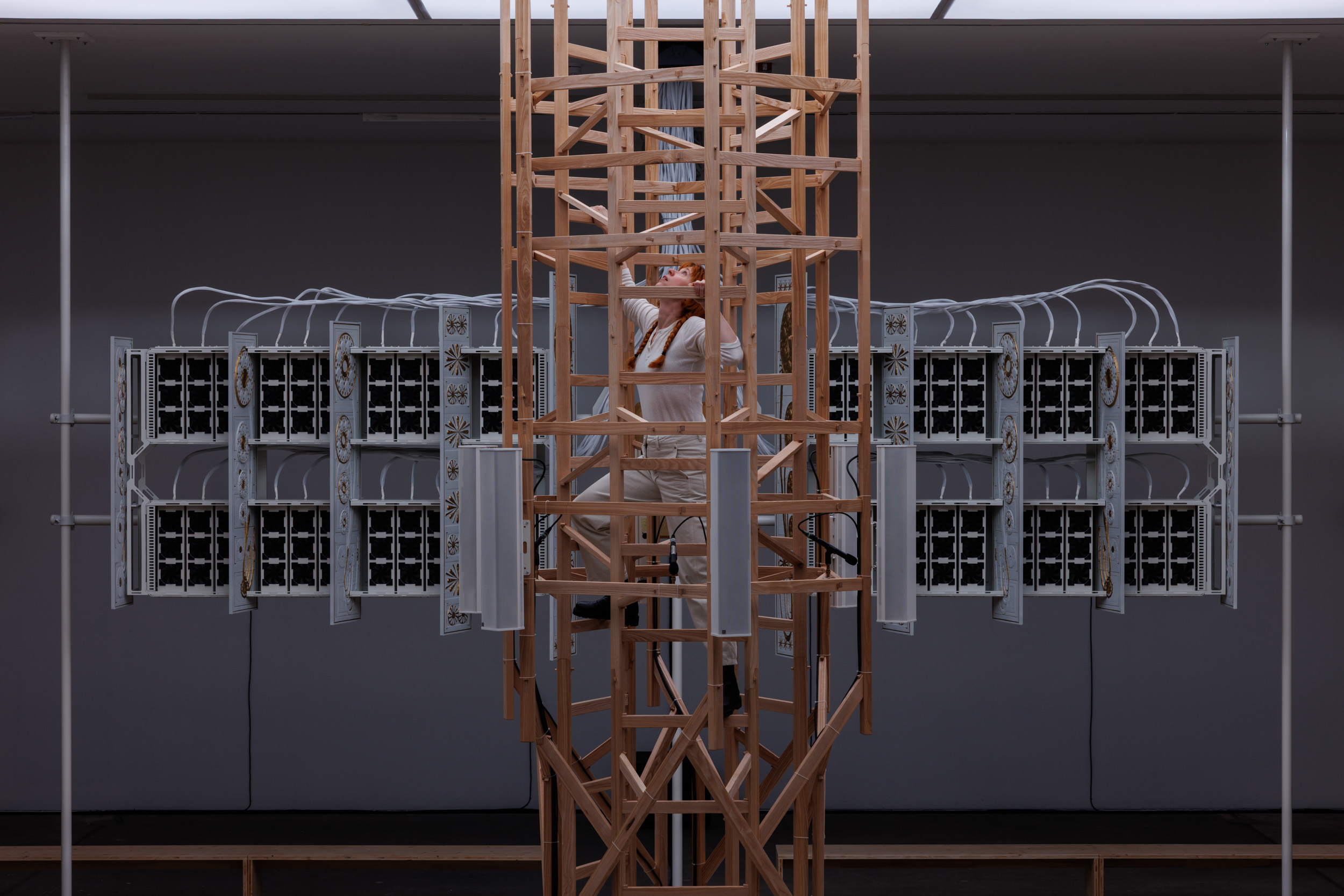

KW is this giant big open space. Bringing it here, we realized we could actually build a space where choirs could come in and sing. We could build an environment where people would want to spend time.

It made us think about the future of public spaces in a post-AI world where we're contributing to models together.

What does that public space look like? This is our gesture towards that.

Mat Dryhurst: Starmirror was our chance to further explore areas we were only alluding to in the UK show but didn't get to really build out. Chief among them is this idea of an AI public space, like Holly said. We have all these different singings that have been really popular, which is wonderful, but people are also using the space. We heard someone the other day say they were hanging out there for two hours and go there to think.

That was the great ambition of the project initially: seeing the exhibition as simulating something that could be permanent, of seeing data centers or this process of training models as something that we all just do now going forward.

It was trying to think of ways to do that with architecture and space that persist in a way that contrasts a lot of AI models that produce mostly ephemera. It's one of their features in some ways. It just produces a bunch of shit.

But Starmirror seems more consistent with where we want this to go, which is actually changing the world around us in IRL.

Holly Herndon: This exhibition also introduces an agent, like the Starmirror agent, who's leading and coordinating the audience. So there's also this new personality or entity to the space that the Serpentine show didn't have.

Peter Bauman: You mentioned the way that you're reimagining Hildegard von Bingen's voice today. Do you think of the voice as a protocol?

Holly Herndon: Voices are really wonderful and I've been obsessed with the voice for decades now with digital vocal processing so it's just a personal interest of mine. But I also think the voice is a really beautiful place to explore some of these ideas of the individual and the collective.

The voice is in this weird in-between space where, yes, you perform your voice with agency as an individual but you learned how to use your voice by mimicking those around you. That's how you learn language and dialect and even just the inflection of your voice.

The voice is like this communal organ that you perform with agency, which I think is a really nice way to think about these models.

Choirs, specifically, are a really good metaphor for showing something that's bigger than the sum of its parts. The simple contributions from individuals can become something really huge and dynamic when all put together. It's a really easy way for people to wrap their heads around this idea of collectivity.

Dealing with medieval music, we don't have recordings from that time. We just have these weird scores that weren't using modern notation; they were using neumes. So already you're translating a neume into a modern notation system and making a lot of assumptions there. You're translating that to something the machine will understand and asking it to pattern recognize. There's some fidelity lost along the way.

Also, the shape of the neume shows the performer the orientation that's embedded in the note rather than writing each note out individually. So each little medieval village or region would have had their own interpretation of those neumes that would have come to life through human beings performing them with each other. It sounds way more microtonal, almost Middle Eastern in nature, than a lot of the Gregorian chant that people think about.

Mat Dryhurst: Neumes as prompts, right? That was one point we were trying to get at with Serpentine and still to this day: people are treating fixed media like it's the law or something.

Our interpretation would posit AI models as cultural technologies that actually work quite similarly to how culture works, which is far less precise. It's far more recombinative and generative in that way.

To bring up Holly's point about Roman and medieval chant, the fascinating thing about it is just the porosity of these different traditions. They're all interpretive. And it's the role of culture to keep that interpretation going rather than it being some weird fixed history.

People are trying to hammer culture down into a file that somebody owns or a particular teleology. Actually, culture is much more slippery and elusive than that. Culture is just an act of doing, where people are constantly reinterpreting things, training themselves on things and then making new stuff.

Holly Herndon: One of the taglines from our book comes to mind: “Don't confuse the media for the art.”

Mat Dryhurst: There's this assumption that the brain is this vast library of references that you store and retrieve. But that's not how our brains work. Our brains are these stigmergic, chaotic processes with neurons with baked-in weights that all have this really simple job. But collectively, intelligence emerges out of your neurons in the same way that a thought emerges out of your neurons.

The room for psychedelia in that is just so delicious.

A lot of our projects are, hopefully somewhat successfully, trying to prompt that psychedelia in others. We want to encourage people to meet this moment with the proper scale of ambition or mutation rather than very boring linear interpretations of AI.

Peter Bauman: You're talking about culture as a process and how these new technologies are changing it in these new ways. Do you have any overall pattern or mental model for how you've seen emerging technologies reshape older forms of culture, like photography and the impact that it had on painting?

Holly Herndon: That's a good question. I think probably the most obvious place where you can find it in music is not so much in a large model output but in algorithmic recommendation. I feel like that has shaped the listener and what gets the most financialization on streaming services.

The radio pushed for the pop song to have a three-minute format. Spotify and the algorithmic recommendation system have pushed musicians to focus right at the beginning so that you have a lower pass-through rate. Also everything's super loud because you don't want to be quiet in the playlist because everything's decontextualized.

Mat Dryhurst: We have an essay from 2022 called “Infinite Images and the Latent Camera,” where we thought about text-to-image’s relationship to photography. The one thing that occurred to us was the history of Pictorialism, when photography moved from something purely scientific to something subjective.

The original criticisms of photography were that it couldn't capture the aura of painting because it was a literal interpretation of the world in front of it. Then the Pictorialists started to experiment and created their own language for expressing subjectivity using things like practical lighting effects.

Then, of course, the history of cinema follows after that. The closest analogy, which I touched on a little bit with Hildegard, is it's closer to the introduction of drugs in the psychedelic period of the mid-century. Of course, that wasn't new either. I mean, mind-altering substances have been used in art for as long as we've been doing stuff.

But our practice tries to provoke this idea that the natural endpoint of art and machine learning doesn't currently have an obvious outcome. Maybe the best takeaway is that change is the only constant.

I would be shocked if in 30 years' time—lord knows where this is going to end up—we're still valuing or exchanging media in the same way that we did in the 1990s. That's just inconceivable to me.

Peter Bauman: Something that spurs change is collaboration, which is baked into your practice. You obviously collaborate together as well as with machine learning technologies, other studios, other artists, the public. How is that entangled “collaborativeness” a reflection of how you see art making moving forward?

Holly Herndon: It's how things have always worked but they’re just increasingly working more and more like that.

If you want to do something really large-scale, you need to collaborate with other people.

Films have always been like this. In the artist studio model, it was just usually one person who got to be the star, but really, it's everyone doing the work. It just goes under one name. I think we try to be a little bit more transparent about how there are all these different intelligences going into our work.

Sometimes we run into some twentieth-century realities where people are so used to the romanticism around what an artist is that when you talk about your collaborator, sometimes they're like, "Well, what are you doing?" That can be really jarring and weird.

Mat Dryhurst: We wrote about this a little bit in the book but it's thinking about compression. There's an understandable compression that would take place in the twentieth century when most people encountered information about art on the printed page, because obviously that has physical dimensions and you can only fit so much information.

The classic example is album covers; in big print on the front you would have the artist's name. Then in small print on the back or on the inside, you would have lots of details about different people who contributed to the project.

It seems to me that the benefit of models is that you can now absorb so much more information in a means that is feasible. It would make sense to credit and celebrate wide contributions in a way that you can do now.

To Holly's point, our position is a positive sum one, which I think also relates nicely to this AI question. I don't feel any less authorship over our work due to the fact that we collaborate with people. It's not a zero-sum game and that's a ridiculous way of looking at culture and always has been.

Fundamentally, what drives me on that is actually a pretty dogged insistence on truth. I don't create too much of a distinction between art and science. I think that it was a mistake to disentangle them and that if they do have a commonality, it’s actually the pursuit of truth through different means.

The idea of groups of people working together to create something remarkable is the story of culture. Subdividing that based on mythologies, or in some cases, quite pernicious misrepresentations, I think is just wrong.

It feels like a duty, in a sense, to try and explore the potential of the new information environment that we're in—to do more good or present more interesting conclusions.

Would future generations know more or less about human culture if viewed from a promotional perspective where one person's name was credited, or if viewed from this positive-sum perspective where all information about how a remarkable cultural achievement happened was made available to that model?

Peter Bauman: I think it also aligns with your ideas on protocols, which I’d like to dig into deeper. First, I see Starmirror or The Call, as sharing as much with traditions of worlding as it does protocols.

These projects create very specific worlds with symbols, rituals, choirs, datasets, sculpture, visuals, architecture, etc. Do you think of the work more like a protocol other people can plug into or as a world people inhabit? How do you see the protocol-world relationship?

Mat Dryhurst: It's a good point and we have talked about the practice as a bit like that for a long time.

The exercise of the records and a lot of the exhibitions has been to build a coherent vantage point that people can come in, interact with, and then in some cases, get lost within.

There's a lot of information, many obscure reference points with us. But the rule set or protocol is that we always are really trying to deliver on it. Whether or not people end up forking and using the Holly+ contract or using the Spawning contract work, we're actually trying to build things in the world that could be used and could be operationalised in that way.

The difference, I'd say to simulated worlds and ours is our goal is to be doing it in real space, as opposed to, say, a contained game environment.

Holly Herndon: This is a tension right now. There are a lot of contemporaries of ours that also struggle with if you have an idea for something, it can be like, “Is this an art project or is this a company?” You have to figure out where it fits and is best suited and then the longevity of it.

I think some of the most interesting work these days is in that weird in-between space where you're trying to figure out where it quite fits.

Mat Dryhurst: That was also the weird, thrilling, blurry line with NFTs, which a lot of people from the traditional art world had a hard time getting their heads around. They were like, “Is this a commercial merchandising operation or is this an art project?” Why not both? It is true; some of the best ideas now are not necessarily constrained by the traditional culture industry’s framing.

Peter Bauman: Building something in the real world goes back to what you said earlier about playing with post-AI ideas of public space. That also allows for public audiences to interact with the work and to maybe come away thinking differently about AI and art.

What are you hoping to achieve regarding public perception of AI? How are you framing the way these technologies will impact expression moving forward?

Holly Herndon: One of the taglines that we've been saying for this show is that “Angels appear as what you fear; devils appear as what you desire.”

We were thinking, “What if all the things people are scared about with AI, except implemented in a good way? What if all of those fears but good? What would that look like?”

Yes, surveillance of everything—but fully encrypted and from publicly available tools. It’s trying to flip things on their heads because the conversation has become so boring in its culture-war format. It has become very for or against. People have put on their team jerseys and shouted for their side. And all the nuance is lost in that.

Mat Dryhurst: With Starmirror, lots of people are coming in and singing. The really interesting basic protocol there is if you don't feel good about having your voice recorded, don't open your mouth. It's very opt in that way.

But people are doing it. They're doing it because they're trusting in the process. It's presenting a real-time experience that you can go into that asks people these threshold questions: Do you trust?

Would you take a leap of faith to be observed by a machine willingly in order to produce something beautiful?

It raises all these interesting questions about IP or privacy, all these liberal, Enlightenment maxims about individualism and privacy and so on.

I've actually come to embrace this term “creator," which I pushed back against for a really long time because it had the stink of not being artistically serious or something. “Creator” presents art and science and engineering all on a level playing field.

What we're seeing is maybe the wind-down of that Liberal Enlightenment distinction between art, science and engineering towards something a bit more eternal that is really a matter of people creating things. The best artists are engineers, the best engineers are artists, et cetera.

The term "creator" probably wasn't intended this way but I'm starting to embrace it for that reason. I think in one hundred years, we'll look back and be like, “Wow, that was a really big shift.” Communication totally shifted around the time of the ubiquitous internet and will mutate into something very, very different from twentieth-century conceptions of art and science. These clean, industrial divisions I just don't think will continue to persist.

Figures, like Demis Hassabis, are just as influential as any of the great artists. And in fact, I would argue they are artists.

Peter Bauman: It reminds me of the cybernetician Heinz von Foerster, who spoke about science as something that separates, including from other fields like art. He preferred his multidisciplinary combination of art and science, which he called systemics.

You mentioned how Starmirror is explicitly engaging with AI’s ethical dilemmas. What do you hope the work contributes to the broader public and art world’s understanding of these debates?

Mat Dryhurst: I'm enthusiastic about people who are curious about where things go. That's a spirit that I associate with art. My feeling is less prescriptive in the sense that I think loads of people have lots of different ideas and thoughts to bring to the table. It’s more about:

We need more people bringing ideas and thoughts to the table. Now is the time for imagination.

That’s for both inside and outside the AI community. On the AI side, there's a preoccupation with previous forms and a tedious reticence at times.

I don't know how you can immerse yourself or dig deep into these subjects and not have your mind blown. It really is wild. I often don't recognize corners of the arts that don't share that feeling.

I don't care what conclusion someone comes to, as long as it's not a reactionary or anti-intellectual slog.

Holly Herndon: I've been overall surprised at the level of groupthink, not just in art but generally speaking. I feel like our bubbles are so intense. Audience capture is one of the biggest problems we have right now. Everyone's just telling people exactly what they want to hear.

Mat Dryhurst: It occurs to me that most of the concerns about AI are better leveled at the attention economy. And actually AI might be a break from that and should be welcomed.

At the same time, Holly and I are really lucky. The institutions we work with have all been super curious and lovely and accommodating. There's a whole world of people, yourself included, who are actually engaging with the present in an open way and trying to come at things without a preconceived conclusion, exploring what this means for culture and art. I'm very optimistic about that winning.

But the most sober analysis is this is what it's like when things are changing: things get stressed and strained; loyalties are tested and people are uncertain. All that I can sympathize with if ultimately the goal is truth-seeking and not some reactionary cope.

So generally speaking, I’m pretty optimistic. But the last few years, between crypto, Ethereum, politics and AI politics, it's definitely been an education in understanding people's tolerance not only for things changing but also for complexity.

Even talking about protocols or these rarefied conversations that we're fortunate enough to be able to have together, you're really asking a lot because it does require a level of abstraction to get where all the action is. Discussing that with someone who's busy, has an active life and hasn't quite thought about it that way or isn't quite inclined to think in that way is really tough.

The challenge at the moment is that there are people selling simple narratives; whether they're doing that sinisterly or not probably differs from individual to individual.

Then there's just the truth that this stuff is really complex and really big and really important to grapple with.

My hope is that we can find space in the realm of art, where traditionally there has been a lot of latitude for complexity and for open-ended exploration.

-----

Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst’s collaborative practice centers uneven distributions of power using AI technologies and virtual ecosystems. The duo are multimedia artists and musicians with Herndon recording experimental studio albums combining electronic music, ASMR, and artificial neural networks, while Dryhurst produces music and creates work in advocacy of a decentralized internet.

Peter Bauman (Monk Antony) is Le Random's editor in chief.