The Ultraintelligent Machine and Gaberbocchus Common Room

The Ultraintelligent Machine and Gaberbocchus Common Room

Jasia Reichardt considers the little-known impact of Gaberbocchus Common Room, London’s first club for artists and scientists, on the development of artificial intelligence (AI). Opening in 1957, the club served as a meeting point for some of the earliest discussions on art, AI and philosophy. The legendary Cybernetic Serendipity (1968) curator muses on its implications for today.

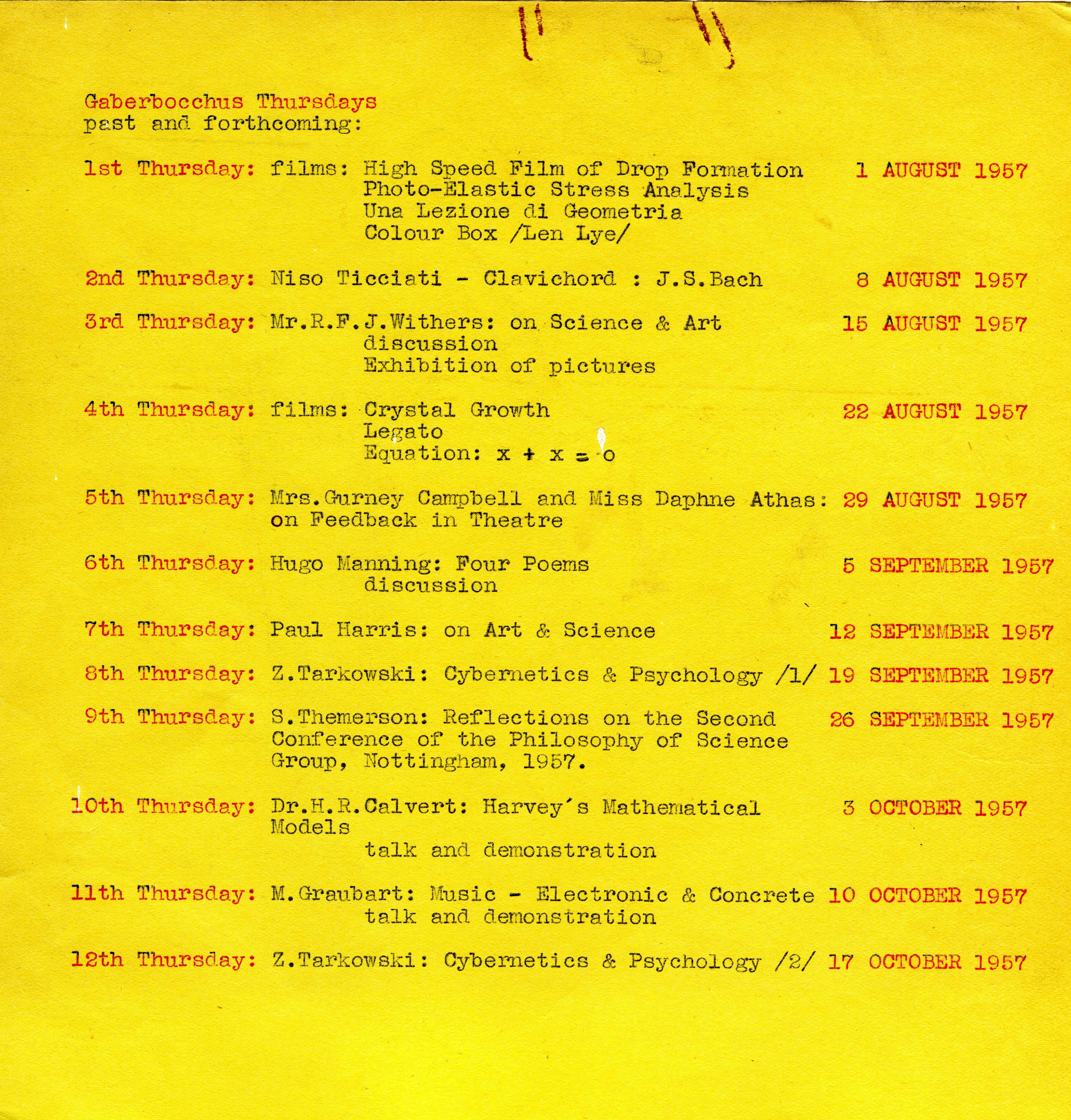

Gaberbocchus Common Room was the first club in London for artists and scientists to meet. It was launched by Franciszka and Stefan Themerson as an adjunct to their publishing company, Gaberbocchus Press, and was active between 1957 and 1959 in a large basement in London’s Maida Vale.

A book about its activities dealing with art, architecture, science, communication, cybernetics, computers, poetry, mathematics, films, plays and experiment of every sort will be out this November [by Reichardt].

Many of the issues presented and discussed at the Common Room are as relevant to us today as they were at the time.

Was there greater optimism of the present leading to the future? Perhaps, but I am not sure. There is a Minute Book of some 300 pages, which was kept with handwritten records by Barbara Wright, with notes describing all the events, including the discussions that followed the lectures. There were also some inserted texts.

The artist Paul Harris talked about Pop Art before the term was used and African masks as a repository of human history. The poet Hugo Manning dwelled on the differences between the language in the heart of the artist and the language in the mind of the scientist. Stefan Themerson reflected on the Philosophy of Science Group in Nottingham, and the poet, Peter Fisk, prepared a special evening in honour of owls.

The consultant in management psychology and personal relations, Z.M.T. Tarkowski, gave 5 lectures on cybernetics and psychology, a bridge between the sciences and the arts. R.F.J. Withers, biologist at the Middlesex Hospital Medical School, explained how science progresses by dismantling previous truths.

The mathematician and cryptologist I.J. Good, a one-time colleague of Turing, wondered whether a machine could make probability judgements and how these would compare with those made by humans.

What I.J. Good talked about at the Common Room was no different than what he talked about to the Philosophy of Science group of the British Society for the History of Science. As was the case with all the discussions, the presentations were not adjusted for a specific audience. Above all, it is the subject that I.J. Good broached that continues to concern us today.

He discussed the reasons why Turing and Shannon considered instructing a general-purpose computer to play chess as a practical proposition even though there was some concern about machines making certain decisions by themselves in a way that humans should not know what they were up to.

AI is there, of course, although not mentioned by name; that had been announced a year before by John McCarthy. Good’s version of AI had a different name. He referred to it as The Machine and supported it with a detailed description. In the Common Room, The Machine was called “it” or “she,” but soon after, I.J. Good chose a new name for this invention and called it the Ultraintelligent Machine. The new name appeared in a published text sometime later in 1965.

At the time, Good anticipated that it could be achieved with support of a large artificial neural net and a million-dollar computer within the twentieth century. The estimated cost, he said, would be £1017. His article with the description starts with the sentence:

“The survival of man depends on the early construction of an ultraintelligent machine,” which will inevitably lead, he continued, to an “intelligence explosion.”

Later he suggests that it will be the last invention that man needs to make, provided it is docile enough “to tell us how to keep it under control.”

The subject thrives on uncertainty. On receiving I.J. Good’s paper about the Ultraintelligent Machine, Stefan Themerson wrote in response that since the it is more intelligent than humans, “we shall not be able to instruct her any further, as ‘she’ would have her own ideas… She could arrive at the conclusion, in the end, that all that bloody business of life is sheer nonsense and the only logical and intelligent answer to it is extinction.”

In a letter to I.J. Good, Stefan Themerson continued as follows:

“One can say that though we should not tell her what to do (in order not to restrict her ultraintelligence), we may still tell her what not to do; for instance:

‘Please, any solution, except Extinction.’

I already hear her answer.

‘Extinction of whom?’

‘Extinction of men!’ we exclaim.

‘Be more precise,’ she says. ‘Give me the definition.’

Now we must watch our step.

If we say, ‘Except featherless bipeds,’ she may produce some plucked peacocks and save them, and not us. And if we say, ‘Intelligent beings’—she may save herself.”

What would be the subjects of discussion of the Common Room of today? AI certainly, but perhaps the adventure of the continuing change in art that is as unexpected as it leaves its various definitions, materials and purposes behind, becomes something else. But, more of that, another time.

JR

-----

The book about the Gaberbocchus Common Room, published by the School of Cybernetics, Australian National University in Canberra, is designed by Pedro Cid Proença and distributed by ArtData.

-----

Jasia Reichardt is an art critic, editor, curator and gallery director with an interest in art's intersection with fields such as technology. In 1968 she curated the landmark Cybernetic Serendipity at the ICA in London, while her latest exhibition, Nearly Human (2015), looked at the history of artificial life.