Sarah Meyohas on Irreducibly Human

Sarah Meyohas on Irreducibly Human

Sarah Meyohas is participating in the group show Infinite Images at the Toledo Museum of Art. In conversation with Peter Bauman (Monk Antony), the artist reflects on her early GAN-driven petal projects and her recent interest in lasting, screen-free works that insist on what remains truly human.

Peter Bauman: Your Cloud of Petals and Infinite Petals have quite a large footprint in one of the main galleries, Infinite Images curator Julia Kaganskiy told me. Can you speak to how those related projects emerged? Did you already have generative models in mind when conceiving Cloud of Petals—or did that evolve later? If so, what drew you to GANs in their very early stages? Which models did you use?

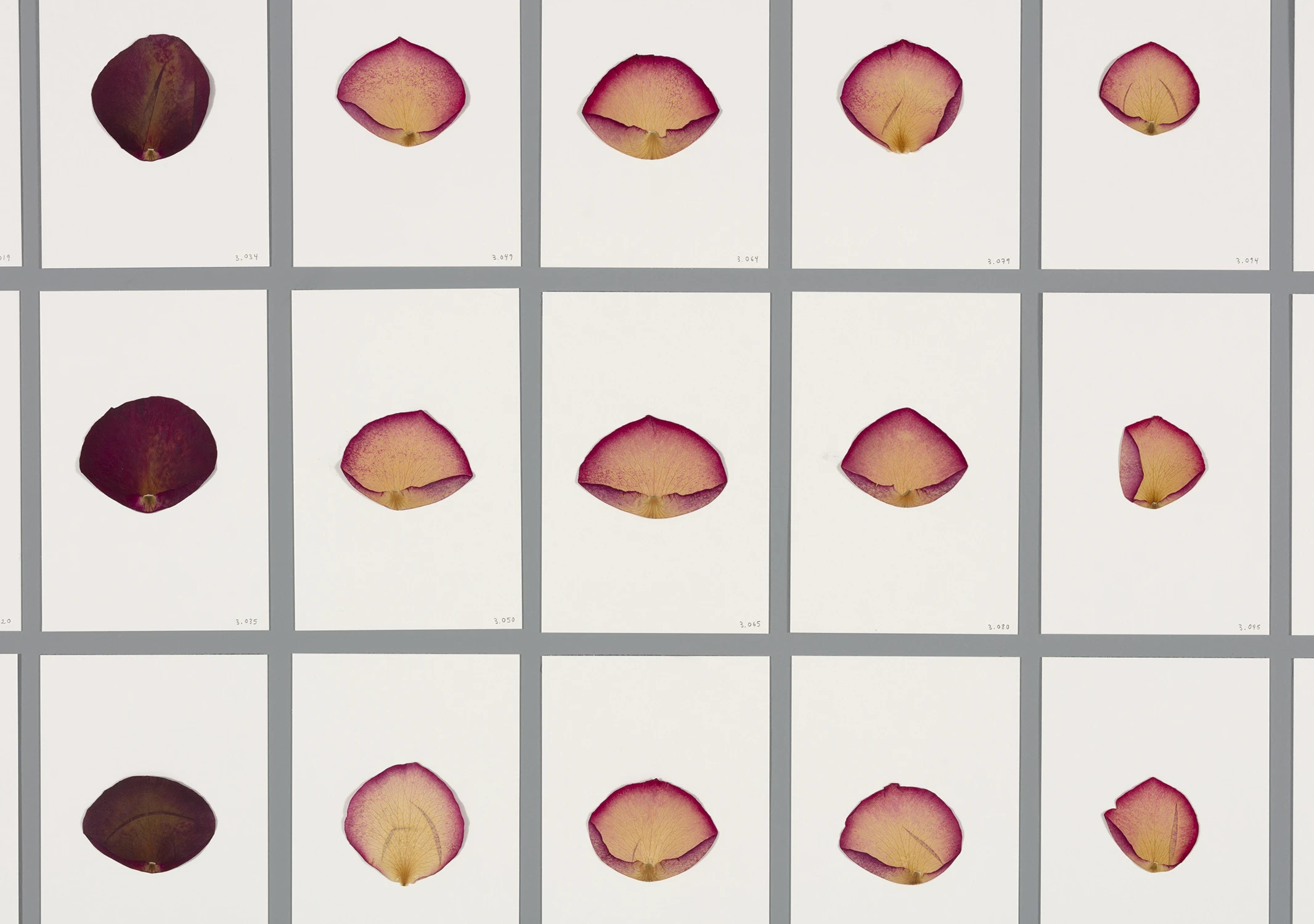

Sarah Meyohas: The dataset came first—that was always the point. In 2016, [for Cloud of Petals] at Bell Labs, sixteen men spent days photographing individual rose petals, amassing an archive of 100,000 images.

This wasn't just documentation; it was the deliberate construction of training data as durational performance.

There was something sublime and incomprehensible to me about that scale. 100,000 of anything feels romantic in its excess, unnatural but effusive. Big data has this quality of overwhelming specificity that tips into the cosmic. I was seduced by the idea that a machine could learn beauty from this mountain of particulars—not classify it, but synthesize it from scratch.

The DCGAN was crude then, almost laughably so, but there was something profound in watching it hallucinate new petals from a learned latent space. Later, with StyleGAN, the control became more granular. I could tune color, manipulate form, and orchestrate the petals into complex geometries. What began as Cloud of Petals evolved into Infinite Petals. Initiated with the same obsession and the same romance of scale but with the algorithm as a more sophisticated collaborator.

Peter Bauman: These two projects in many ways also relate to Bitchcoin, a work that similarly explored value systems through emerging technologies. What’s the through line for you between working with blockchain, GANs and large datasets? How did those tools help articulate your artistic concerns at the time?

Sarah Meyohas: Both works dissect the statistical underpinnings of desire but they also share an obsession with making invisible systems brutally explicit. When I first encountered blockchain technology, I found it remarkable as a raw creation outside of all existing systems and a new form of value emerging from pure mathematics and collective belief.

Bitchcoin embodied the art market's financialization to such an extreme degree that it became impossible to ignore.

While Warhol opened a factory in 1962, I designed a financial instrument in 2015. That shift says everything about how capital accumulation has changed, foregrounding speculation over production.

The art market operates as a hybrid of antagonistic value regimes and I wanted to distill that dynamic into something a viewer could more readily interact with and trade.

With the petals, the same logic applies. I’m rendering the process visible. What you see is the labor: sixteen men, days of work and 100,000 individual photographs. Machine learning isn't hidden in some black box; it's the direct result of this absurdly massive human effort.

Both works ask, what happens when you make the invisible mechanisms of value creation so apparent—to such a poetic extreme—that they become the art itself?

The through line is about embodying these systems to such a poetic extreme that they become visible.

Peter Bauman: These “invisible mechanisms” of creation are what Infinite Images foregrounds, particularly how artists engage with systems and automation.

But recently, your work has focused more on material permanence—toward works that, as you’ve said to Art Basel, “speak to someone directly in the moment” but that also “in 300 years, they will still work.” This seems like a departure from the software-dependent nature of your earlier work, like the Petals series. Are timelessness and the digital at odds in your view?

Sarah Meyohas: This is more complicated than it appears, revealing our deep confusion about what digital even means. We often conflate the material output of a work with its production process but my approach to producing physical objects has become increasingly digital. Truth Arrives in Slanted Beams would have been impossible without extensive computation and modeling. The plotters and the sculptures I'm developing all rely on heavy-duty digital processes that remain invisible in the final work.

The real issue isn't digital versus physical—it's dependency.

The longevity of a work is further challenged when an artwork is beholden to a corporation and subject to software updates. Art as a momentary experience can survive such fragility but art as an artifact demands a different kind of autonomy.

I try to create works that exist independently, and as a result, can last as long as their form allows them to.

Of course, we’re also inundated with screens and the screen inevitably becomes another layer of mediation between the viewer and the work, which I find phenomenologically lacking if it’s not fundamental to the project. Sometimes this is unavoidable, as with Cloud of Petals and Infinite Petals.

Otherwise, the holograms are my rebellion against this flattening, as they are difficult to accurately document, though they can be replayed by a single light beam from a particular angle and experienced for centuries. Maybe you could call that an algorithm of sorts.

With much of my recent work, I’m looking to bypass the screen entirely to create an embodied experience in a world of endless reproduction.

Peter Bauman: You’ve also described your approach as using technology not for its own sake, but to create experiences that “don’t otherwise exist.” How do you see the artist’s role today—especially when working with generative systems that can feel increasingly autonomous or impersonal?

Sarah Meyohas: AI has barely touched artistic practice itself; it remains largely peripheral to how most artists actually work. What it has transformed is image culture, social media and the broader visual ecosystem that surrounds art. This peripheral transformation creates its own pressures. When AI dominates every conversation, we inevitably view existing artworks through this new lens—a recalibration that's warranted, given that AI represents a genuine watershed in human history.

AI’s real impact isn't on art but on the art world's relevance.

Images are not inherently artworks. Art operates as a self-reflective cultural practice, distinct from mere image production. When AI floods the market with endless visual content, it colonizes the visual landscape in ways that compress art's territory. The channels through which art moves become clogged with machine-generated content.

This is precisely why the artist's role becomes creating despite this proliferation—not to merely use generative models but to create in response to their existence.

I use technology when it helps me create experiences that don't otherwise exist but my strategy now is making things that could not even be in any dataset. Take my holograms; they resist digitization entirely, exist only in physical space and demand your bodily presence. Training data cannot replicate that phenomenological encounter.

This approach is important to me because it asserts that human experience still exceeds algorithmic capture. When I create something that exists outside any possible dataset, I'm insisting that consciousness, materiality and lived experience contain elements that simply cannot be computationally reproduced.

It's a resistance that doesn't reject technology but insists on what remains irreducibly human.

---

Sarah Meyohas is a conceptual artist whose practice considers the nature and capabilities of emerging technologies in contemporary society. Using the familiar emblems of biological life, Meyohas investigates the complex operations that increasingly govern our world.

Peter Bauman (Monk Antony) is Le Random's editor in chief.