Object Misrecognition

Object Misrecognition

Luba Elliott observes how a growing number of artists are subverting facial and object recognition, using the foundational AI technologies’ flaws and rigid categorizations to explore the aesthetic collisions between machine vision and human perception.

AI art today is largely associated with generative systems that create images, texts and videos, prompted only by a few words. Meanwhile, facial and object recognition, other foundational AI technologies, frequently lie forgotten—but not entirely.

A group of artists specifically interrogates facial and object recognition just as the technologies increasingly become embedded in our daily lives. These artists explore themes like misrecognition, hallucination and categorization errors—not simply to generate pleasing images but to scrutinize the differences and unexpected affinities between human and machine perception. They ask us to reconsider the aesthetic and epistemological foundations of how we see and how machines see for us, beginning with our most personal feature, our faces.

Recognizing the Face

Humanity’s interest in portraying one’s likeness has meant an ongoing search for understanding the face’s structure and meaning for thousands of years, often aligned with the latest scientific advancements. Since Neolithic times, scars and tattoos have been regarded as markers of identification. Early modern developments in facial recognition originate in the work of Woody Bledsoe’s research team from the 1960s, whose technology required manual marking of facial features before the computer was able to recognize a face. In 1970, one of the first public uses of facial recognition technology took place at the Osaka Expo in Japan, where attendees could have their faces scanned, classified and matched to seven celebrity types at the installation Computer Physiognomy, developed by Nippon Electric Company. Presented then as a demonstration of a future technology that would later penetrate our lives through its surveillance capabilities, the moment has arrived. Surveillance is now widely applied in the public realm, including airport passport control and protestor identification.

Surveillance to Subversion

These contemporary applications of facial recognition technologies have inspired concern in artist circles, with artist-activists confronting issues associated with their usage. Opportunities for the evasion of the face—disguise strategies and obfuscation—can be found in Adam Harvey’s CV Dazzle (2010) and follow-up project HyperFace (2017), a tool for blending facial textures into the surroundings. These works show that as machine perception grows more accurate, artists must continually evolve their tactics, experimenting with jewelry, masks, costume elements and projection-based camouflage. Meanwhile, research on the application of facial recognition in fine art remains limited.

This holds particularly true when the technology moves beyond representational portraiture and becomes an exploratory tool for examining the differences between human and machine perception.

Misrecognition as Method

Contemporary photography, selfie culture and social media have enabled the face to be depicted in a realistic likeness on a mass scale like never before. Shinseungback Kimyonghun’s work Nonfacial Portrait (2018) subverts this notion of realism by commissioning portrait painters to work alongside a facial recognition system to create portraits that are not AI recognizable. This project turns surveillance on its head.

Instead of being watched, we survey the way the facial recognition process functions, delighting at its efforts and errors as we see the accompanying video of portrait-making.

One might be surprised to notice the many interpretations of a portrait that come out of this project. Some have facial features misplaced; others consist of a repetition of the human face multiple times—rotated at an angle of 90 degrees. Yet others rely on color to sculpt the shape of the nose from the rest of the face. At that point the face stops being seen as a face to the machine.

To the human beholder, it is possible to detect a face in many of these portraits because the breadth of the depiction of the human form—from photorealism to figurative art to abstraction—has trained our visual perception system on what may constitute a portrait. In a peculiar fashion, certain portraits recall the early images generated by generative adversarial networks (GANs), in which the misplacement of eyes and ears was a common feature. This perceptual flexibility is echoed in Matty Mariansky’s Evolutionary Faces (2020), where a curve generator evolves line drawings toward face-likeness, hovering at the edge of both machine and human recognition.

Hallucinating Machines

Faces can also be seen in places where there are none, a phenomenon known as pareidolia. Kimyonghun’s Cloud Face (2012) explores the ability of machines to recognize faces in clouds erroneously, while Driessens & Verstappen’s Pareidolia (2019) relies on an automated robotic search engine to locate faces in grains of sand.

In our anthropocentric view of the world, we search for the familiarity of the human face in impossible locations and have now trained machines to follow in our footsteps by misrecognizing clouds, sand and more.

Algorithmic pareidolia extends beyond the face in DeepDream, where a neural network recognizes features and objects not in the original image and amplifies them to create the multicolored hallucinatory puppyslug images we have come to associate with the aesthetic. Today, pareidolia is a recurring theme of interest, with a slew of papers and artworks presented at computer vision conferences, including Lee Butterman’s Stable Diffusion Clock (2023), Scott Allen’s Unreal Pareidolia -shadows- (2023) and Daniel Geng et al.’s Visual Anagrams (2014). They all playfully explore the latest technologies to expose how humans and machines can trick each other.

Jessica Tucker’s work could almost be reverse pareidolia. The artist’s face features heavily as input for multiple projects, including pooling (2024) and cycles (2024). In pooling, new faces generated from the artist’s distorted selfies are collaged together into animations that evoke lava lamps. This visual allusion recalls the randomness harnessed in Cloudflare’s lava lamp encryption wall—another attempt to obscure and evade predictability in a rigid system. Tucker’s use of computer-generated fractal noise—typically used to simulate natural shapes and motion—for the collaging process enables a similar idea of making oneself indeterminate, hiding from machine vision, in a society where everything is tracked.

In cycles, the face is used as input to generate a stream of bodies. These are then animated using motion capture data from the artist and a life-size dummy ragdoll, resulting in unusual aesthetics where a recognizable face is paired with a body that departs into simplified, abstracted form. Tucker lays bare the limits of machine perception and extrapolation: with the predominant textural input being the face, it is a challenge to correctly reproduce the human body.

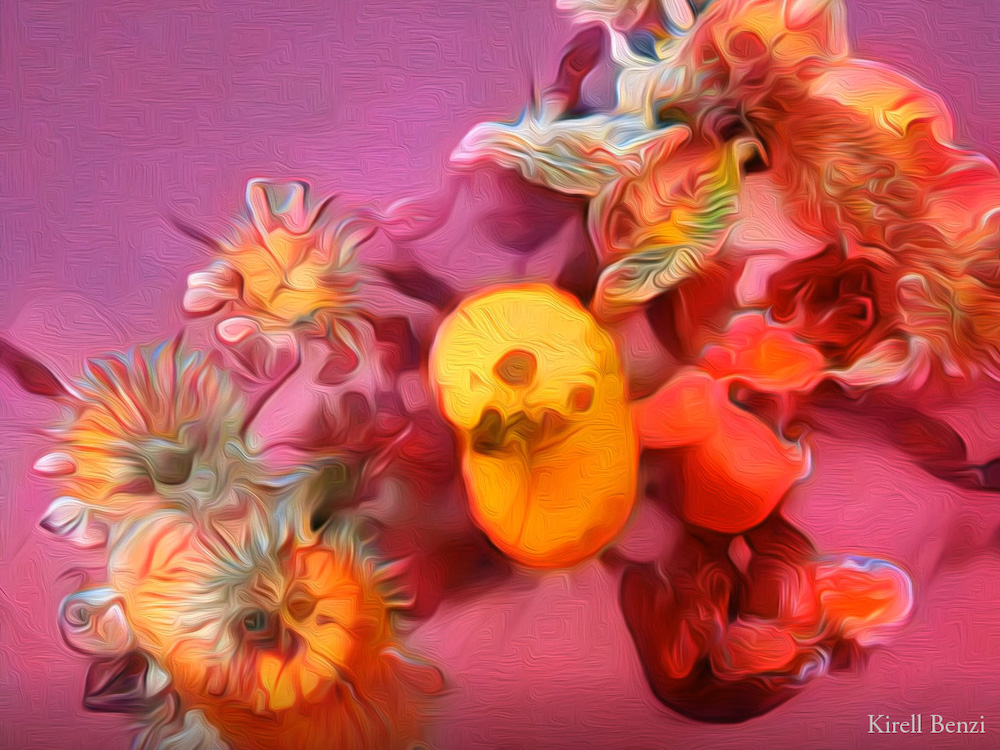

Beyond the body, a similar interest in object construction can be observed in Kirell Benzi’s ‘These are not flowers’ (2020), in which we see colorful flowers shapeshift from one type into another. Numbers run alongside the moving image, referring to the weight of each object type—such as strawberry, bell pepper or guinea pig—that has been used to generate each frame. Notably, none of these belong to a flower category.

This mismatch underscores how machine learning systems can detect visual similarities—such as color or texture—between otherwise unrelated categories, like guinea pigs and flowers, in ways that may seem surprising to human viewers. Unexpected connections like this can be found in the Italian studio Fabrica’s 2016 Tate IK prize-winning work, Recognition. The project drew parallels between contemporary photojournalism and art from the Tate Britain’s collection, resulting in such matches as car seats compared to Henry Moore sculptures and modern laptop users compared to scholars writing at the desk.

Unlike Benzi’s work, these examples are connected by shape and broader scene context, providing stronger figurative links between object classes. They highlight how machine vision can be guided to make associations based on narrowly defined criteria—often ones that humans would overlook or never consider.

Artists engaging with facial and object recognition in the fine arts can work imaginatively with the technology by testing its functionality outside of realism, questioning the assumptions behind categorization and collaborating on a mutual understanding of the world. By highlighting the misalignments and parallels between human and machine perception, these artists open up new ways of seeing—ones that question not just how machines interpret the world, but how we teach them to do so. Ultimately, they invite us to look beyond the surface of the machine gaze and into its full perceptual process, invigorating how we see and make sense of both art and everyday life.

-----

Luba Elliott is a curator and researcher specializing in creative AI. She works to engage the broader public about the developments in creative AI through talks, events and exhibitions at venues across the art, business and technology spectrum, including The Serpentine Galleries, V&A Museum, Feral File, ZKM Karlsruhe, Impakt Festival, NeurIPS and CVPR.