Karl Sims & Alexander Mordvintsev on Merging Technology and Biology

Karl Sims & Alexander Mordvintsev on Merging Technology and Biology

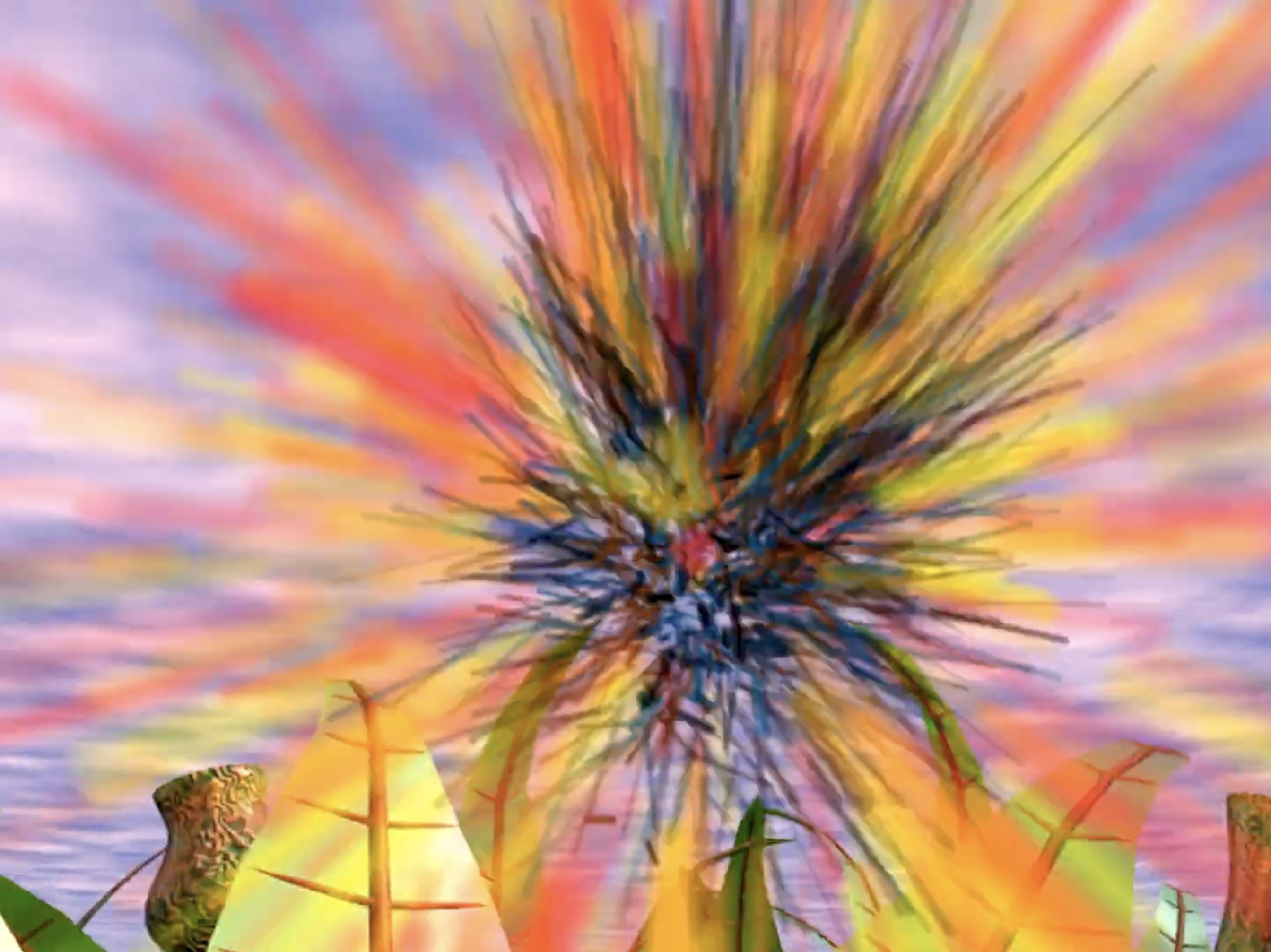

Artists and engineers Karl Sims and Alexander Mordvintsev speak about the potential of artificial life (A-Life) and creativity with Peter Bauman (Monk Antony). They discuss A-Life as a bridge between technology and biology, from Sims’s early work with the legendary Connection Machine and Evolved Virtual Creatures to Mordvintsev’s seminal DeepDream.

Alexander Mordvintsev: Karl, there are things I’ve wanted to ask from the bottom of my heart. You have been in the field of A-Life pretty much from its foundation. Well, of course, Conway was a bit earlier [laughs].

But some people in this field hope that A-Life may eventually become a large part of our technology, of our civilization. Technology and biology will merge eventually. And A-Life, I sometimes like to think about it as NeurIPS twenty years ago when no one cared. Do you see this happening or do you think it will stay niche?

Karl Sims: No, I think it's happening. It’s broad, but like a lot of things:

The hype wave tends to overcome reality for a while and then fade out. But then reality trudges on and eventually it becomes significant and interesting.

Where are we now? I don't know. It depends on which piece of the pie you're talking about.

Alexander Mordvintsev: To me, it's the dream of being able to build complex things right from the material sources that are around, like trees that build themselves from the thin air and what they find in the ground.

In general, I’m talking about having manufacturing capability that is close to what nature is capable of in terms of fidelity of structures produced, adaptivity and ability to use what's present rather than bringing special types of materials from the other end of the world.

But in the short term, I mean making what we were doing in the digital—playing on computers, being able to build complex worlds out of nothing—happen in the real world. Karl, can you talk about how nature inspired you?

Karl Sims: Nature is a huge inspiration for me in many ways. The evolutionary process is interesting to simulate but also the many types of complexity in nature that can essentially emerge on their own are fantastic. Simulating these types of processes to generate new and unexpected results has always been a passion of mine.

Alexander Mordvintsev: What are you working on now?

Karl Sims: At the moment, I have a couple projects. I've been installing a few museum exhibits with real-time interactive visual effects. I have some pieces at the Museum of Science in Boston, one at MIT, and one at the Museum of Mathematics in New York. Plus I’m installing one at the Boston Children's Hospital. These involve fluid flow, particle systems, reaction diffusion, and so on, simulated in real time so visitors can play around and experiment.

I'm also working on a WebGPU-based application for image synthesis and special effects, replicating some of the types of things I was doing ever since Connection Machine days but now are much easier on the web. That's a longer-term project though so I don't have much specific to say about it yet.

Peter Bauman: Alex brought up your mutual connection to nature and representation, which leads to the very beginning of your story, Karl, because you studied life sciences at MIT. But fascinatingly, you went on to this incredibly forward-thinking organization, Thinking Machines, which is like an early OpenAI or Anthropic today.

How did a degree in life sciences lead you to this radically experimental early AI company?

Karl Sims: Right. Yeah. They weren't hiring a lot of biology majors.

When I was an undergrad, I was also very interested in computer science and computer graphics. I took classes in that as well, even though it wasn't my official major. I also had an internship at the Architecture Machine Group, which later became the MIT Media Lab. So when I graduated, I already had some experience with computer graphics. My roommate was Brewster Kahle, who was at Thinking Machines at the time and went on to found the Internet Archive later on. He introduced me to Danny Hillis and the gang at Thinking Machines and I ended up joining them and trying to figure out how to program this crazy new parallel computer—to make pictures and computer animation with it.

I actually worked at Thinking Machines twice. After a while, I returned to the MIT Media Lab for a graduate degree, then worked in Hollywood for a while, and then returned to Thinking Machines. I was jumping around a little but was actually just following these Connection Machines. The Hollywood firm was an early customer and the Media Lab had also acquired one.

Alexander Mordvintsev: I'm mostly curious about the environment at Thinking Machines. For me, this has very practical implications because I'm trying to manage a little group and Thinking Machines is a place to look up to.

Karl Sims: They suffered a little from being too early. I think they were about twenty years too early in making a proper GPU. They ended up closing around 1994 but it was a great place with amazing, wonderful people.

Early on, they didn’t have a machine built yet so it was all simulators, which were rather slow, but we had to start thinking about how to program parallel computers, which turned out to be very interesting and useful later on. We were at this beautiful Thomas Paine estate out in Waltham, Massachusetts, and it was a great environment that felt very academic. Later on, they had working hardware so I could really do things on it, which was quite fun.

I was the “Artist in Residence” and my job was to show off the computer in a visual way with simulations and graphics and so on.

I wrote a number of graphics tools and made some experimental animation pieces. I was also finding bugs in software, reporting them, giving feedback on things, and just helping everybody test the software out as we were developing this new computer. It became a larger company but it was still a great place to work. A lot of interesting scientists around the world participated because this computer allowed new simulations and database work that hadn't been possible before.

Alexander Mordvintsev: Which languages did you use to program it? I understand you had to invent the programming from scratch.

Karl Sims: Correct, we had various options for programming it. We started out taking existing languages—like C, Fortran, Lisp—and making parallel versions of those that could run on all the different processors. It was a bit like programming a GPU these days.

Alexander Mordvintsev: I read an anecdote that, once upon a time, Richard Feynman came there and used some pretty unconventional ODE-based approaches to model message passing on the Connection Machine. Were you there around that time?

Karl Sims: I was there when Feynman was there and I got to interact with him a bit. He was a fun character and always glad to give feedback on the puzzle of the moment.

Peter Bauman: You mentioned your experience at Thinking Machines was part engineer and part artist. Just on a philosophical level, how do you both see the difference between science and art? Karl, what were you doing in that year of residency?

Karl Sims: They mix together well. Scientists can help artists with tools and artists can help scientists communicate visually. I think they can be combined nicely.

Alexander Mordvintsev: I have my personal take on that.

It's art when you don't have to explain the trick; it's science when you show that what you did is sufficiently similar to something someone did before.

Peter Bauman: That’s good! You both invented these really early tools. Alex, you with DeepDream, and Karl, your many tools over the years. You both want to show what new technologies are capable of but you also are expressing yourself creatively. How do you distinguish between those two things?

Alexander Mordvintsev: Well, I honestly don't. I never distinguished the two. I was doing my thing. This whole story of neural networks is mostly about when things designed for one purpose make something you don't expect them to do.

That is pretty much the same as Karl’s work, Evolved Virtual Creatures. You just set up the universe, describe the rules, and then you see them evolve and do stuff you didn't directly program. Maybe there is some parallel there.

Karl Sims: Yes, indeed.

Alexander Mordvintsev: Karl, what are your feelings on the history of computing and the way it unfolded? Were there any other possibilities? Connection Machine, which later became GPUs, as well as ideas like ConvNets, were already published in the '80s. They were mostly not paid attention to because technology wasn't ready. Do you think there are any other gems hidden in piles of old publications?

Has everything that you wanted to see materialized or do you think there are things yet to be rediscovered?

Karl Sims: I think there's still plenty to be discovered. In general, I feel like it's even more fun to write software these days; it's easier. The tools are better; computers are faster.

The kids these days don't appreciate what they have.

We used to have to work pretty hard to create with a computer because it was expensive and it was hard to get time on supercomputers, especially as an artist. We had to write our own software but it was worth it. We were trying new things and it was great. These days it seems easy, relatively speaking.

Alexander Mordvintsev: Yeah, but on the other hand, computers are so destructive these days. I'm from ex-Soviet Union so my childhood computers in the '90s were approximately computers in the West from the 1980s.

My childhood was formed by Z80-based machines, ZX Spectrums and clones of early Intel CPUs. When you see what those can do, you understand, “This is cool,” but you have to program many things from scratch.

So actually it was somehow easier to get addicted to tinkering with stuff rather than in our world now, where there are so many disruptors and things that require your attention.

Karl Sims: That is true. There are many more computers but most are just used rather than programmed. People are less creative with them, typically. They just use them to communicate and share stuff rather than create new things.

Alexander Mordvintsev: On the other hand, I see some fantastic people who still do very non-trivial work. It's not super widely appreciated but there are small communities that I think are still well and carrying this fire; they continue to invent new things. For me, Shadertoy was one such community.

What do you think? Is there something that is being lost over time? Or do you see that still there is sufficient creativity that happens around computing? Are there communities that are not afraid of getting down to basics and squeezing the maximum?

Karl Sims: Of course there are many people still being quite creative with computers. There's no doubt about that. But there are also many people that I think are "getting programmed" by computers instead of creating with them, which I think can be a problem for our culture.

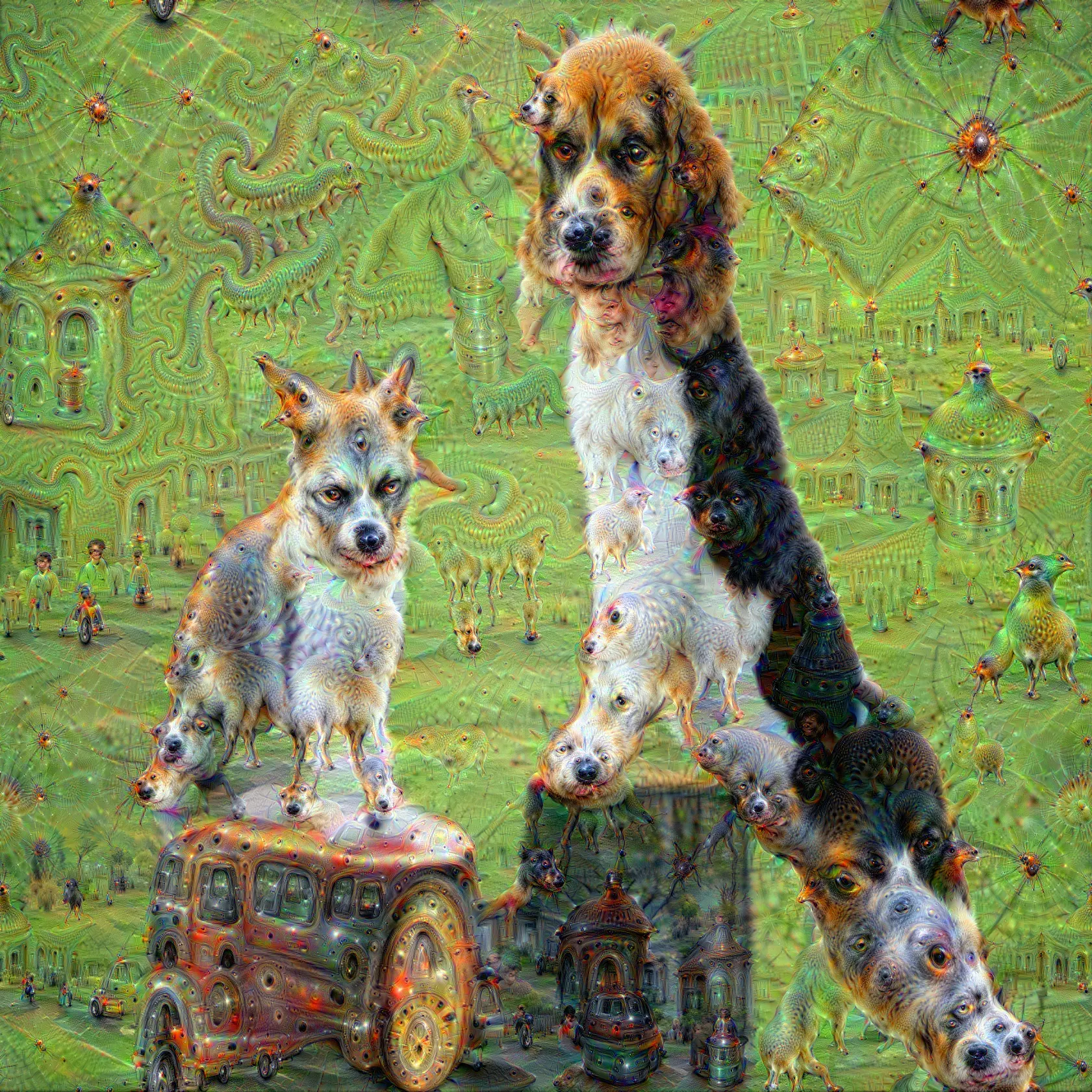

Peter Bauman: Both your work has been so crucial to the development of neural networks and creativity. Karl, in many ways it started with Evolved Virtual Creatures and Alex, your DeepDream (2015) was critical to the popularization of deep learning and creativity.

But are you surprised that there was such a long gap (thirty years) between Karl’s early experiments and when they really took off creatively with Alex’s work in 2015?

Karl Sims: Well, that's interesting. There's a pretty big difference in what we were doing, though. I was not using neural networks to create things. I was using genetic algorithms to create neural nets rather than the other way around, if that makes any sense.

Take the virtual creatures project as an example. It used machine learning and it used neural nets but in a very different way than, I think, either LLMs or DeepDream. I was doing the evolutionary simulation where random mutations were made to these graphs that generated neural nets, which then generated the creatures and their behaviors.

I think there's a commonality in that both can generate complexity in a way that you would have a lot of trouble designing by hand but they’re also pretty different.

People often ask, “What are the similarities and differences between the virtual creatures and what AI can do now?” They're pretty different.

I feel like a lot of the current AI work doesn't necessarily “invent” new things very well.

They're taking huge databases as a starting point and using those to generate things quickly, which can be very interesting and sometimes very useful. But oftentimes, I think they can't explore totally new ideas so well because they're just relying on existing data.

Whereas, in theory, evolutionary algorithms can invent completely new, different things that you wouldn't have thought of or predicted because they're not based on existing data. They just try things at random with natural selection or artificial selection feedback. Then they try more things at random and iterate and build on that. I think it's quite different in that way. Maybe LLMs and current AI can somehow incorporate some of that too but typically I don't think they do.

Alexander Mordvintsev: First of all, I totally agree with what you're saying. Also, I wanted to make a little comment about my role because I think Peter a bit overstated the impact of DeepDream. What I was doing back then was probably one of the first times the general public saw recent neural nets that were coming from the computer vision community, which is quite a niche thing if you compare it with the whole population. But they had been tinkering with them for a couple of years already.

Those things can produce some artifacts that are not similar to anything the world has seen before. And this was what triggered that tidal wave ten years ago. My contribution was quite small. It just increased awareness and wrapped things that were proven in the community in a form that was accessible to the public.

Speaking of evolution, this is a great point. In our group, over the last couple of years, we experimented with evolution and, in particular, with evolutions of short programs in esoteric languages. And this is a constant source of surprises. With neural nets, you have this giant system and you are surprised that it does things that it was not trained to do. But it's a giant system.

But with evolution, you start with very simple rules and you see emerging behaviors that you didn't expect. One of the biggest struggles the A-Life field has had over the years is what we call accumulation of complexity because of all the open-endedness.

All the simulations that you observe that the community is trying to build usually hit ceilings of complexity that the simulated world allows. They struggle to build something beyond that.

What's missing in the way we do evolution in artificial life that prevents us from reaching open-endedness, which would essentially mean that the longer you run, the more complex structures you get. Rather than now, where we are hitting some glass ceiling and not developing beyond that.

Karl Sims: To back up a little bit, I wouldn't minimize your contribution because I feel even if something might feel a little bit incremental, it still affects the next thing, which affects the next thing. So it can still have a very big contribution in the end, just like evolution itself.

Each little mutation can make all the difference because it gets built upon.

For your point about reaching open-endedness, for a while, you could argue that computer resources were a limiting factor. That becomes less and less so, however. I guess now it would be more about what's the genetic language you're using? What's the programming language you're trying to evolve things or create things in? Make sure that that's sufficiently open-ended and evolvable.

Peter Bauman: Alex, can you talk about which elements of your work have been inspired by Karl?

Alexander Mordvintsev: I can't say that the specific DeepDream experiment was inspired by Karl's work. But what came later definitely was.

My subsequent work and especially my current interest that I’ve worked on over the last few years is in self-organization and artificial life. But even earlier, what people called CPPNs, compositional pattern producing networks, is something that Karl pioneered. You could make a compositional function that takes coordinates of some point in space and produces color.

This is a very powerful way to represent various signals, such as images. I started experimenting with them as a way to represent images to feed into neural networks and then do this process in reverse, like taking a neural network that produces an image and feeding this image into a pre-trained net. Then you try to maximize a particular hidden feature of that net by modifying the parameters of a tiny neural network that produced that image.

This leads to very high fidelity, interesting images with rich structure. In a sense, CPPN served as a prior for modeling images that have a structure in them.

What happened later with these ideas was the whole hype with Neural Radiance Fields, where instead of parameterizing points in the image, you just took points in space and had a neural network that, given this point, produced material properties. Then you do classical raycasting through this space. To me, it stems from Karl's work, which was subsequently developed by people like Kenneth Stanley and others.

Peter Bauman: What has surprised you both about the development of neural nets?

Alexander Mordvintsev: Sometimes I imagine what would happen if I traveled back in time and happened to see Evolving Virtual Creatures in the mid-90s. I would have felt, “Wow, locomotion, robotic locomotion! Lifelike agility of robots is around the corner.”

And somehow this is only starting to be realized and on completely different principles.

Karl Sims: Well, these days people are thinking that artificial general intelligence is right around the corner but I don't think that's true.

Alexander Mordvintsev: My personal take on that is humans don't possess general intelligence. So the whole AGI is a myth.

Peter Bauman: Karl, can you talk about starting GenArts and the impact that it would go on to have on generative art with all these generative algorithms that you helped pioneer, including particle systems and reaction diffusion? They’ve had such a hidden impact on culture when you consider their extensive use in the popular media of the last century: film, television, video and video games.

Karl Sims: So GenArts was a company I founded in 1996, and we developed and sold a product called Sapphire Plug-ins, which consisted of a couple hundred visual effects and image processing tools that worked with Avid, Flame, Adobe After Effects, etc.

Users could easily load in their digital clips and process them, adding glows, glints, lens flares and so forth. I wouldn't say there's a direct connection with artificial life at all, but the tools were helping people be visually creative so that was rewarding.

Peter Bauman: How did your development of tooling compare with how it's done today?

Karl Sims: It was different because I was creating the tools as well as using them. These days, you can mess around with these AI tools without having a clue how they work.

Alexander Mordvintsev: In addition to what you said, Peter, Karl may not even know his impact on media by influencing the Demoscene.

Some decades ago, I was pretty excited about it and really inspired by its style of thinking. Demoscene is a community of people who create computer game demos. It must be a program that shows some interesting, beautiful audiovisual effect on a screen. Usually, there are categories, like a program that has to be less than 64 kilobytes or even below 4 kilobytes.

This community experiments a lot with things that stem from your work. They use a lot of reaction diffusion and particle systems. Actually, it's quite a niche subculture but they have quite big events. The demoscene learned a lot from Karl.

-----

Karl Sims is a digital media artist and visual effects software developer. His interactive works have been exhibited worldwide including at the Pompidou Center, Ars Electronica, DeCordova Museum, Boston Museum of Science, and the National Museum of Mathematics.

Alexander Mordvintsev is an artist and machine learning engineer, who is passionate about emergent phenomena, computer graphics and machine vision. He loves visualizing things and is best known for inventing Google DeepDream.

Peter Bauman (Monk Antony) is Le Random's editor in chief.